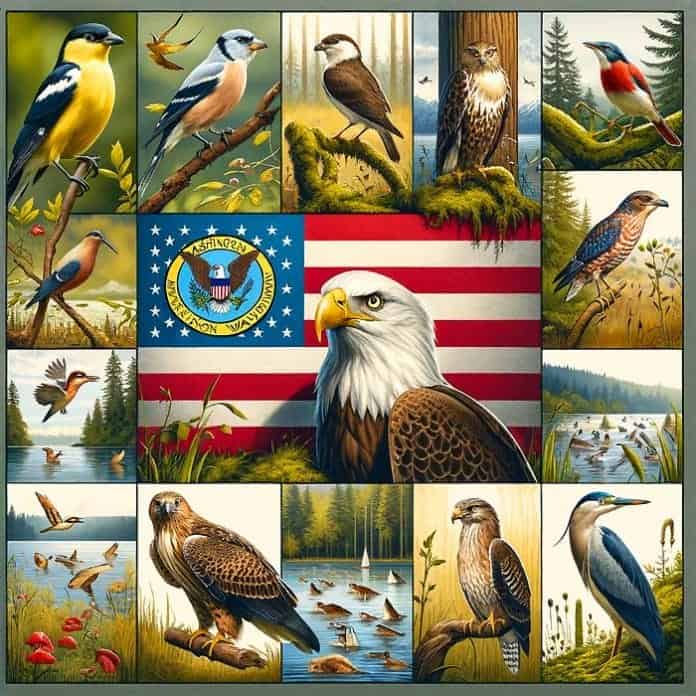

Washington Birds: Washington state is a premier birding destination with varied habitats ranging from coastal rainforests to high mountain peaks. Over 450 bird species have been recorded in Washington, providing birders ample opportunities to spot both resident and migratory species.

Washington’s most sought-after birds include the Bald Eagle, the Northern Spotted Owl, the Snowy Owl, the Sandhill Crane, and the vibrant Western Tanager. From backyards and city parks to wildlife refuges and rugged wilderness, birds can be observed across the state.

This article explores a diverse selection of 26 must-see birds in Washington. For each bird profiled, facts, physical features, habitat, range maps, and viewing tips are provided to aid identification. Whether you’re a seasoned birder or just starting out, use this guide to help locate and observe these remarkable winged creatures in the wild.

The list encompasses songbirds, raptors, waterfowl, owls, and more. Refer to this guide when planning a birding adventure in Washington to make the most of your time in the field. With so many incredible birds inhabiting the forests, mountains, lakes, and coastline, you will surely be dazzled by Washington’s vibrant avifauna.

Table of Contents

- Washington State Ecology and Habitats

- Top Birds of Washington State

- 1. The American Goldfinch: A Symbol of Washington’s Natural Splendor

- 2. The Pine Siskin: Washington’s Nomadic Songbird

- 3. Adaptability and Resilience of the House Finch in Washington

- 4. The Purple Finch: A Colorful Denizen of Washington’s Forests

- 5. The Red Crossbill: A Unique Avian Adaptation

- 6. Cassin’s Finch: A Harmonious Presence in Washington’s Ecosystem

- 7. Evening Grosbeak: A Striking Bird in Washington’s Wilderness

- 8. The Bald Eagle: Washington’s Majestic Raptor

- 9. Cooper’s Hawk: A Stealthy Predator of Washington’s Skies

- 10. The Osprey: A Majestic Fisherman of Washington’s Waters

- 11. The Red-tailed Hawk: A Predatory Icon of Washington’s Skies

- 12. The Peregrine Falcon: A Remarkable Avian Predator

- 13. The Merlin: Agile Hunter of the Skies

- 14. The Sharp-shinned Hawk: A Nimble Hunter of Washington’s Forests

- 15. The American Kestrel: A Dazzling Predator of the Skies

- 16. The Golden Eagle: A Regal Presence in Washington’s Skies

- 17. The Barred Owl: A Mysterious Nocturnal Hunter

- 18. The Great Horned Owl: An Iconic Night Hunter

- 19. The Western Screech-Owl: A Cryptic Denizen of Washington’s Forests

- 20. The Snowy Owl: A Mesmerizing Winter Visitor

- 21. The Northern Saw-whet Owl: A Secretive Nocturnal Hunter

- 22. The Northern Pygmy-Owl: A Pint-Sized Predator with a Big Presence

- 23. The Great Blue Heron: A Stately Presence in Washington’s Waterscapes

- 24. The Nuthatch: Washington’s Agile Tree Navigator

- 25. The Sandhill Crane: A Graceful Migrant of Washington’s Wetlands

- 26. The Western Tanager: A Colorful Harbinger of Summer

- Frequently Asked Questions

- What is a common bird in Washington State?

- Where can I find a list of birds in the state of Washington?

- How can I attract birds in Washington State to my bird feeder?

- What is the Nuthatch, a bird in Washington?

- Are there any aggressive birds in Washington state?

- What types of bird feeders are common in Washington State?

- What is the house sparrow, a common bird in Washington?

- How do birds in Washington State nest?

- What do young birds in Washington State eat?

- Are there bird-watching societies in the state of Washington?

- Conclusion

Washington State Ecology and Habitats

Washington State’s extensive forests, shrublands and alpine zones create critical shelters sustaining varied bird communities.

- Coastal woodlands filled with Douglas firs and hemlocks offer copious cover and insects for canopy dwellers, while sparse interior grasslands camouflage ground nests of shrikes and sage grouse. Even urbanizing areas must conserve native foliage to preserve increasingly imperiled warbler and sparrow refuges from relentless encroachment.

- Across biomes, specific vegetation shapes avian density and diversity. A 2020[1] Journal of Urban ecology study showed introduced trees fail to match native cedars and firs hosting far richer native chickadee, nuthatch and woodpecker assemblys.

- Central Washington’s arid shrublands likewise see greater sage grouse and sharp-tailed grouse thriving where intact sagebrush persists, though habitat fragmentation jeopardizes these shrubsteppe specialists.

- Shelter specifics also matter Northwestern Naturalist researchers in 2003[2] discovered mature high-elevation pines with ample nest hollows are white-headed woodpecker bastions. However, widespread logging of large-diameter snags and decadent elders could irreparably unravel Eastern Cascade sanctums for these already Near Threatened excavators.

- Even in lower valleys facing agriculture incursions, a 2012 Condor paper found curtailing brush clearing sustains vital Lazuli Bunting and grasshopper sparrow niches.

Balancing preservation with relentless pressures demands expanding insight into faunal tipping points. A 2006 Journal of Urban Ecology analysis highlighted that beyond sheer habitat area, structural complexity and spatial configuration crucially impact urbanizing bird communities.

This emerging frontier for conservation ecology seeks to situate species within finely calibrated environmental gradients – research urgently needed to frame protection policies as more greenery vanishes under roads and concrete each year.

Top Birds of Washington State

1. The American Goldfinch: A Symbol of Washington’s Natural Splendor

| Animalia | Passeriformes | Fringillidae | Spinus | Spinus tristis |

The American Goldfinch (Spinus tristis) is a small finch found throughout Washington state. It is also the state bird of Washington. Males have bright yellow plumage on the body and black wings, while females are dull brown. They make a pleasant musical sound and feed on thistle and sunflower seeds. These finches live in open areas like fields and backyards.

The American Goldfinch is a small finch, with males with wingspan ranging from 8 to 11 inches. Females are typically dull brown in coloration. These finches emit a pleasant musical warbling sound and often feed on thistle, sunflower, birch, and alder seeds. American Goldfinches can be found in weedy fields, orchards, and backyards across Washington state, thriving in open environments with seed sources.

The bright colors and sweet song of the American Goldfinch make it a beloved backyard visitor in Washington. As a state bird, it is a common sight foraging on seeds in gardens and parks. Goldfinches particularly enjoy fields overgrown with weeds, which provide ample food. Their ability to thrive around humans makes them a delightful addition to any backyard.

American Goldfinch Facts

- A study from Eastern Michigan University examines the partial migration habits of these western WA birds, revealing how stress hormones may influence their seasonal movements. This survival strategy showcases their adaptability.

- Their choice of feeder locations, important for their foraging strategy, has been studied for its impact on their survival, highlighting the importance of understanding avian preferences in urban and suburban environments.

- The male Goldfinch’s vivid yellow color, crucial for attracting mates, is directly linked to dietary carotenoids. The intricacies of this relationship are detailed in a study published in Comparative Biochemistry and Physiology Part B: Biochemistry and molecular biology, shedding light on the significance of diet in their mating success.

- Moreover, their social interactions, particularly agonistic displays used to establish dominance, have been the focus of research featured in Behavior, offering insights into their complex social structures.

2. The Pine Siskin: Washington’s Nomadic Songbird

| Animalia | Passeriformes | Fringillidae | Spinus | Spinus pinus |

The Pine Siskin (Spinus pinus) is a small North American finch in coniferous and mixed forests across Washington state. They have streaky brown plumage with some yellow on the wings and tail. Their diet consists mainly of conifer seeds from trees like hemlock, spruce, pine, and larch. Pine siskins are social birds that may forage in large flocks, especially in winter.

The pine siskin is a small finch with streaky brown and yellow plumage. It feeds primarily on conifer seeds, favoring hemlock, spruce, pine, larch, and fir trees. Pine siskins flock together while foraging, sometimes forming large groups in the winter. They inhabit coniferous and mixed forests throughout Washington and some urban areas with conifer trees. As a migrant species, their numbers fluctuate in the state depending on food availability farther north.

Pine siskins may descend on Washington forests in great numbers during winter, consuming vast quantities of conifer seeds. In other years, when conifer crops are abundant farther north, only small flocks may migrate down. The busy flocks, with their distinctive wheezy calls and Yellow wing bars, bring lively activity to the conifers in winter. Pine siskins are a mobile species, wandering the state for ample food sources.

Pine Siskin Facts

- These birds native to Washington state are cherished for their lively social interactions and melodic songs, resonating through their preferred woodland habitats.

- A notable study on these birds, detailed in the Journal of Experimental Biology, sheds light on their response to food scarcity. Contrary to many species that prepare for lean times, Pine Siskins are likelier to leave their current habitat in search of better conditions, exemplifying an ‘escape’ strategy rather than a ‘preparative’ one.

- Furthermore, the approach of spring triggers a fascinating biological change in these birds, as seen in research published in Royal Society Open Science. With increasing daylight hours, Pine Siskins begin to show migratory behaviors, gearing up for their seasonal movements.

3. Adaptability and Resilience of the House Finch in Washington

| Animalia | Passeriformes | Fringillidae | Haemorhous | Haemorhous mexicanus |

The House Finch (Haemorhous mexicanus) is a small bird native to western North America that was introduced to Washington and many other areas of North America. The male has bright red plumage on the head, upper breast, and rump, while females are brown with light streaking. House finches live around human settlements and scavenge for food in backyards and gardens.

Native to the western United States, the house finch has reddish-colored males and brown females with streaking. They were introduced to the East Coast and have become established near towns across North America. House finches scavenge for food sources like buds, seeds, and insects in urban and suburban areas like parks and backyards. They may form large flocks in the winter.

The house finch is now abundant and widespread in both urban and rural areas of Washington. These very social birds form flocks and can always be found near humans. Their adaptability allows them to use ornamental plants and bird feeders for food. The cheerful red plumage of male house finches livens up backyards and gardens year-round across the state.

House Finch Facts

- A study published in Behavior reveals that urban House Finches exhibit less aversion to novel noises than their rural counterparts, demonstrating their successful adaptation to the hustle and bustle of urban life. This research provides insight into how these birds have adjusted to human-dominated landscapes.

- The health of House Finches is also a focus of research, particularly about Mycoplasma gallisepticum, a bacterium that causes conjunctivitis. An article in The Auk delves into the dynamics of this infection, offering a glimpse into the challenges these birds face in varying environments.

- Research in Behavioral Ecology and Sociobiology explores the antipredator strategies of House Finches in urban settings. This study suggests that urban areas might provide safer environments from predators, even when humans are present, highlighting the birds’ ability to find safety in human-altered landscapes.

4. The Purple Finch: A Colorful Denizen of Washington’s Forests

| Animalia | Passeriformes | Fringillidae | Haemorhous | Haemorhous purpureus |

The Purple Finch (Haemorhous purpureus) is a reddish finch found across Washington and much of North America. Males have bright raspberry-red plumage on the head, breast, and rump, while females are streaked brown with some red on the head and breast. They inhabit forests across the state and feed on seeds, buds, and fruits.

The male purple finch has bright red plumage on the head, breast, and rump, while the female is brown with lighter streaking. Their habitat is forested areas, including both conifers and deciduous trees. Purple finches mainly eat seeds, buds, nectar, and fruits from trees and plants. They breed in northern forests, and many migrate south for the winter.

Purple finches occur in Washington year-round as a breeding species and overwintering migrants. They inhabit coniferous and mixed forests across the state. Flocks feed on tree seeds and fruits, with their sharp beaks allowing them to access hidden seeds. In late winter, they are attracted to tree sap. The red males singing from high perches are a splash of color among the evergreens.

These birds of central washington construct intricate nests in conifer branches made from twigs, bark, moss, and plant down. The female incubates 3-6 bluish eggs for 12-14 days while the male brings food. Both parents feed the nestlings. Predators include squirrels, blue jays, and Accipiter hawks. Nest parasitism by brown-headed cowbirds can also impact reproductive success.

Purple Finch Facts

- As for many bird species, the threat of disease is a significant concern for the Purple Finch. A study in Avian Diseases explores whether Purple Finches might be the next host for a mycoplasmal conjunctivitis epidemic, a disease that has significantly impacted House Finches. This research indicates the potential for cross-species transmission of pathogens in avian populations.

- The Purple Finch’s population genetics and connectivity are also areas of scientific interest. A study published in Ecology and evolution reveals that purple finches exhibit population genetic isolation and limited connectivity, which could affect their conservation and management. This research underscores the importance of understanding genetic Diversity in maintaining healthy populations.

- The Purple Finch is not just a colorful addition to Washington’s avian community but also a species of interest in disease transmission and population Genetics studies.

Overall, purple finches thrive across Washington’s varied forest ecosystems. These colorful songbirds brighten mountain forests and backyard woodlands with red plumage and lively energy.

5. The Red Crossbill: A Unique Avian Adaptation

| Animalia | Passeriformes | Fringillidae | Loxia | Loxia curvirostra |

The Red Crossbill (Loxia curvirostra) is a distinctive finch species found across coniferous forest habitats in Washington state. They get their name from the crossed mandibles of their bill used for extracting seeds. Males are red-colored with darker wing markings, while females are yellowish-green with some reddish hues.

This is a specially adapted finch species whose crossed bill allows them to efficiently pry seeds out of conifer cones. The male red crossbill is bright brick-red with darker wings and tail, while the female is olive-green with some red, especially on the head, rump, or breast. They feed on conifer seeds but also some insects and tree sap. Their breeding habitat spans northern coniferous forests, and they often wander nomadically based on cone crops.

In Washington state, red crossbills occupy higher elevation conifer forests across the Cascades and northern interior ranges. These finches adeptly extract the seeds of hemlock, spruce, fir, pine, and other conifers using their distinctive crossed bills. They are somewhat nomadic in following mature cone crops, with numbers fluctuating in any region. Red crossbills may also descend to lower elevations and feeders in winter.

These Washington state birds breed early in the year while snow still blankets much of their mountain habitat. They nest in dense conifers, with females building a nest of twigs, bark strips, and moss in a horizontal tree fork. The male feeds the incubating female as she lays 3-4 eggs. Both parents feed the young. Despite challenges in their specialized niche, red crossbill populations currently appear secure across their range. These unique birds bring vibrant flashes of red to Washington’s conifer forests year-round.

Red Crossbill Facts

- A recent study in Ibis explores the fast cultural evolution of Crossbill calls, highlighting their vocalizations’ remarkable adaptability and variation. This study sheds light on the complex communication system of these birds and their ability to modify calls rapidly in response to environmental changes.

- Another intriguing aspect of the Red Crossbill is its plumage, which varies in color intensity. Research in bioRxiv reveals that wild common crossbills produce redder body feathers when their wings are clipped, indicating a fascinating link between physical condition and plumage coloration. This finding suggests that the feathers’ redness may signal individual quality or health status.

- The Red Crossbill in Washington is a testament to evolutionary ingenuity, showcasing specialized feeding adaptations and a complex communication system.

These studies provide a glimpse into this species’ unique characteristics and adaptability to ever-changing environments.

6. Cassin’s Finch: A Harmonious Presence in Washington’s Ecosystem

| Animalia | Passeriformes | Fringillidae | Haemorhous | Haemorhous Cassinii |

Cassin’s Finch (Haemorhous cassinii) is a reddish-brown finch found in western North American forests, including coniferous and mixed woodlands in Washington state. The male has a bright red crown and upper breast, while females are streaked brown without red. They feed on conifer seeds and eat buds, fruits, and insects.

The male Cassin’s finch has a bright red crown, nape, and upper breast, contrasting with its brown back and wings. The more drab female lacks red and is light brown with dark streaking. This species mainly eats conifer seeds and buds from hemlock, spruce, fir, and pine trees. However, when available, it supplements its diet with fruit, berries, and some insects. Its breeding habitat encompasses conifer and mixed forests of the western mountains.

In Washington, Cassin’s finches largely occupy higher-elevation conifer forests such as those found on the eastern slopes of the Cascades. However, they also utilize lower-elevation pine and mixed woodlands locally across the state. These lively songbirds feed actively in flocks, foraging for conifer seeds and educational material. While generally remaining in the interior West year-round, some Cassin’s finches migrate altitudinally within mountain ranges or to lower elevations in winter.

The breeding ecology of Cassin’s finches’ centers upon conifer seed crops. They build an open cup nest of plant fibers lined with hair or feathers on a horizontal conifer tree branch, laying 3-6 eggs. Both parents incubate the eggs and feed the young. crows, jays, squirrels, and accipiters will take eggs from nests. Cassin’s finch populations appear secure currently throughout their range.

Cassin’s Finch Facts

- The males of this species boast a beautiful red color, which intensifies during the breeding season, while females and juveniles display a more muted, brown-streaked appearance.

- Inhabiting coniferous forests and mixed woodlands, Cassin’s Finch primarily feeds on seeds, especially from conifers, supplemented by insects and berries. This diet plays a crucial role in seed dispersal, aiding the health and regeneration of forest ecosystems.

- A captivating aspect of Cassin’s Finch is its song, a high-pitched, warbling melody that varies among individuals. This variation aids in avoiding confusion with other species and enhances individual recognition. Their songs, most prominent during the breeding season, are vital for mating rituals and territorial defense.

- A study focusing on the songs of Cassin’s and Plumbeous Vireos provides insights into the complex acoustic communications of Cassin’s Finch, underscoring the significance of bird songs in their ecology and Behavior. These songs play a pivotal role in mating and territorial behaviors.

7. Evening Grosbeak: A Striking Bird in Washington’s Wilderness

| Animalia | Passeriformes | Fringillidae | Coccothraustes | Coccothraustes vespertinus |

The Evening Grosbeak (Coccothraustes vespertinus) is a stocky finch species with a massive conical bill found in forested areas of Washington. Males have yellow-green plumage with a brown back and black tails, while females are grayish-green with yellow foreheads. These grosbeaks often travel and forage in flocks, feeding mostly on tree seeds, buds, and some insects.

The male evening grosbeak has bright yellow-green and white plumage with a brown back and black tail and wings. Females are primarily grayish-green with a yellow forehead. Their huge bills are adapted for crushing hard seeds. Evening grosbeaks eat tree seeds like Maple, boxelder, ash, buds, and insects. They breed in northern coniferous and mixed forests and migrate irregularly farther south in winter.

In Washington state, evening grosbeaks occupy higher-elevation conifer forests but descend to lower elevations and feeders in winter months. They travel in noisy flocks seeking out tree seeds. The grosbeaks’ large size and brilliant golden coloring make them stand out among other feeder birds. However, their numbers fluctuate annually in Washington depending on food sources farther north. When spruce budworm outbreaks allow successful breeding, the next winter may see more evening grosbeaks migrating down into the state.

Evening grosbeaks build a tightly woven nest of twigs high in a conifer tree, upon which the female lays 3-4 pale blue or greenish eggs speckled with brown. The male feeds the incubating female as she faithfully tends to the eggs. Though striking birds, some populations are in decline due to climate change shrinking their preferred northern boreal habitat.

Evening Grosbeak Facts

- A study published in Diversity reports dramatic declines in Evening Grosbeak numbers at spring migration stopover sites. This significant decrease highlights the urgent need for conservation efforts to protect these birds and their habitats.

- Another intriguing aspect of the Evening Grosbeak is its unique crown coloration. A report in Northwestern Naturalist discusses an individual with an unusual crown coloration, adding to the understanding of the species’ variability and plumage diversity.

- The Evening Grosbeak’s diet mainly consists of seeds, especially during winter. They are known for their hearty appetites and can often be seen at bird feeders, where they congregate in large, noisy groups.

- With its striking appearance and social behavior, the Evening Grosbeak is a notable presence in Washington’s avian community. However, the observed decline in their numbers is a cause for concern, emphasizing the need for continued research and conservation efforts to ensure their survival.

8. The Bald Eagle: Washington’s Majestic Raptor

| Animalia | accipitriformes | Accipitridae | Haliaeetus | Haliaeetus leucocephalus |

The Bald Eagle (Haliaeetus leucocephalus) is a large bird of prey and the national symbol of the United States. In Washington, bald eagles are found along coastlines, large lakes, and rivers across the state. They have distinctive brown bodies, bright white heads and tails, and massive yellow beaks. Their diet is primarily fish but includes mammals and carrion.

Identifiable by its white head and tail, large yellow beak, and brown body plumage, the bald eagle is one of the largest raptor species in North America. They mainly prey on fish but also eat waterfowl, gulls, mammals up to the size of foxes or fawns, and carrion. Bald eagles mate for life and build immense nests high in large trees. They live in areas with access to open water foraging, including coasts, lakes, and rivers.

Many bald eagles reside year-round along Washington’s marine coastlines, major rivers, lakes, and reservoirs. Salmon and other fish compose the majority of their diet. Bald eagles also migrate through the state and overwinter along rivers and lakes. Their enormous nests built high in tall trees dot shorelines across Washington. Prime viewing locations include the Skagit River, Lake Roosevelt National Recreation Area, and the San Juan Islands.

The Washington Department of Fish and Wildlife notes the importance of protecting habitat for the continuity of sustainable bald eagle populations. Critical breeding habitats deserve conservation focus, as human activity can disturb nest sites. Though no longer endangered, bald eagles face threats like lead bullets, pesticides, and habitat loss. As Washington’s state bird, the iconic bald eagle inspires local conservation efforts across its range.

Bald Eagle Facts

- A study in the Science of The Total Environment addresses the seasonal threat of lead exposure in Bald Eagles. This research highlights a significant environmental concern, as lead poisoning from ingested ammunition and fishing tackle poses a grave risk to these birds.

- Another issue facing Bald Eagles is the impact of ingested lead on populations in New York State, as discussed in the Wildlife Society Bulletin. This study provides critical insights into the consequences of environmental contaminants on eagle populations, emphasizing the need for conservation and policy changes.

- Bald Eagles are primarily fish eaters, often seen soaring near water bodies or perched in tall trees. They are also known to scavenge and prey on small mammals and birds. These birds’ majestic flight and hunting prowess make them a captivating sight for birdwatchers and nature enthusiasts.

The Bald Eagle in Washington represents natural beauty and power and faces significant environmental challenges. Research on lead exposure and its impact underscores the importance of conservation efforts to protect this iconic species.

9. Cooper’s Hawk: A Stealthy Predator of Washington’s Skies

| Animalia | Accipitriformes | Accipitridae | Accipiter | Accipiter cooperii |

Cooper’s Hawks (Accipiter cooperii) are crow-sized woodland hawks found across forest and woodland habitats in Washington state. Adults have blue-gray upperparts with reddish barring on the belly and wing undersides. These sharp-shinned accipiters can fly through dense cover to ambush small bird prey.

About the size of crows, Cooper’s hawks have blue-gray backs and reddish bars on the lighter undersides. Their long tails and rounded wings allow maneuverability in chasing bird prey inside forests. They mainly eat small birds caught in rapid pursuit flights and mammals, insects, and reptiles. Cooper’s hawks nest in tall trees, laying 3-6 eggs.

In Washington, Cooper’s hawks occupy forests and woodlands statewide. They often perch quietly before bursting through dense vegetation in pursuit of unwary songbirds. Cooper’s hawks typically breed in stands of tall Douglas fir, pine, or other conifers near feeding areas. Nests are well-concealed high on a horizontal tree limb.

The number of breeding pairs currently appears healthy. However, widespread logging and land conversion depleted populations in the early last century. As urban forests expand, adaptability may allow Cooper’s hawks to thrive. However, bird feeders may concentrate prey and increase attacks. Sharp flashes of a pursuing hawk inside tree canopies thrill observant birders across Washington’s wooded parks and forests.

Cooper’s Hawk Facts

- A study in Ecosphere presents an integrated population model highlighting intersexual differences in the life history strategies of Cooper’s Hawks. This research provides valuable insights into the unique breeding and survival strategies between male and female hawks, emphasizing the complexity of their life cycles.

- An intriguing aspect of Cooper’s Hawk behavior is their vocalization, particularly during the breeding season. The Journal of Raptor Research discusses an undocumented vocalization of adult male breeding Cooper’s Hawks, suggesting this call may be exclusively used for communication with their young. This study sheds light on the nuanced communication systems within raptor species.

- Cooper’s Hawks are known for their adaptability to various habitats, including urban environments. Their ability to thrive in diverse landscapes has made them a subject of interest in urban ecology.

- A study published in the American Midland Naturalist explores whether there are differences in ecological attributes and reproductive output of yearling female Cooper’s Hawks breeding in urban versus rural landscapes in Wisconsin. This research highlights the impact of habitat on the breeding success and Behavior of these birds.

The Cooper’s Hawk in Washington is not just a remarkable predator but also a fascinating subject of scientific research. These studies provide a deeper understanding of their breeding strategies, communication patterns, and adaptability to changing environments.

10. The Osprey: A Majestic Fisherman of Washington’s Waters

| Animalia | Accipitriformes | Pandionidae | Pandion | Pandion haliaetus |

The Osprey (Pandion haliaetus) is a large fish-eating hawk found widely along Washington state’s waterways, lakes, and coastlines. They have white undersides, brown upperparts, a white head with a dark eye stripe, and long, narrow wings. Using specialized feet, ospreys dive to catch live fish at the water’s surface.

Sometimes called a fish hawk or fish eagle, the Osprey has brown plumage with a white head and breast. Their long, angled wings allow adept maneuvering to catch fish in extended talons. Ospreys eat mostly live fish and build immense nests in dead trees or platforms near water. They winter along coastal areas farther south before migrating back to northern breeding habitats.

In Washington, ospreys occupy lakes, reservoirs, rivers, and marine shorelines across the state for breeding and migrating habitat. Their primary diet best aids them in bioindicating contaminant concentrations in Washington’s watersheds over time. Breeding sites center around bodies of water up to around 2,000 feet. Nesting begins in April as paired birds engage in dramatic courtship flights and calls.

By late summer, Washington osprey numbers increase as migrants join local breeders on fishing grounds regionally. Though still common statewide, habitat loss and organochlorine pesticides have induced significant declines in the last century. Nesting platforms helped recovery efforts for this unique raptor, making ospreys a conservation success story in Washington. Their wide distribution across diverse waterways is key to monitoring ecosystem changes over time.

Osprey Facts

- These birds are superb fishers, often seen diving feet-first to catch fish in lakes, rivers, and coastal waters.

- One of the significant studies on Ospreys involves their genetic variability and family relationships. Published in Diversity, this research provides insights into the genetic makeup and family dynamics of a reintroduced Osprey population, highlighting the importance of genetic Diversity for the conservation of this species.

- Ospreys are also known for their adaptability, especially in nesting habits. A study from Northwestern Naturalist documents the Ospreys’ shift from nesting in trees to artificial structures in the San Francisco Bay Area, California, showcasing their ability to thrive in changing environments.

- In Washington, the Osprey symbolizes the state’s rich aquatic ecosystems. These birds contribute to the ecological balance by controlling fish populations and serve as indicators of the health of water bodies. Their presence along Washington’s waterways provides a spectacle for birdwatchers and an opportunity for scientific study and environmental education.

The studies on Ospreys underscore the intricate relationship between these birds and their habitats and the importance of conservation efforts to ensure their continued presence in Washington’s skies.

11. The Red-tailed Hawk: A Predatory Icon of Washington’s Skies

| Animalia | Accipitriformes | Accipitridae | Buteo | Buteo jamaicensis |

The Red-tailed Hawk (Buteo jamaicensis) is a common large raptor in Washington known for its distinctive ruddy tail. They have a variable plumage with whitish underparts and bright bellybands on a mostly brown back. Red-tailed hawks adapt well to diverse habitats when hunting small mammals, birds, and reptiles.

The red-tailed hawk is a stocky buteo hawk with pale undersides and brownish upperparts ranging from paler to almost black. Their namesake cinnamon-red tail is seen in flight or perched. They primarily prey on voles and other small mammals but regularly eat birds, snakes, and insects. Red-tailed hawks often soar over open country and may perch visibly on poles, trees, or the ground.

In Washington, red-tailed hawks occupy habitats ranging from mixed conifer forests to shrub steppe and prairies statewide up to around 8,000 feet elevation. They adjust well to logging and land-use changes. The broad range of acceptable nesting spots aids their success as Washington’s most common hawk.

In contrast to a darker back, the broad red tail and pale belly help identify soaring red-tailed hawks in Washington’s skies. They often nest conspicuously in dense trees along habitat edges for an ample view hunting the surrounding land. Resident pairs maintain breeding territories year-round, only leaving when deep mountain snow cover makes finding prey impossible. Strictly protected for most of last century, red-tailed hawk numbers rebounded across North America and remain consistent in Washington habitats statewide.

Red-tailed Hawk Facts

- A notable study in the Journal of Wildlife Diseases has found that the Red-tailed Hawk is a native definitive host of Frenkelia microti, a type of parasite. This research offers crucial insights into the hawk’s role in the ecosystem and its interactions with parasitic organisms. Understanding such relationships is crucial for conservation and wildlife management.

- The hawk’s reproductive success is influenced by its habitat, as shown in a Journal of Wildlife Management study. This research highlights how urban and suburban environments impact the breeding success of Red-tailed Hawks, providing valuable information for urban wildlife management.

- Red-tailed Hawks are apex predators, feeding primarily on small mammals, birds, and reptiles. Their hunting skills, characterized by soaring flight and sudden dives to capture prey, testify to their adaptability and prowess as predators. They play a crucial role in controlling rodent populations and maintaining ecological balance.

The Red-tailed Hawk symbolizes the wild and is an essential component of diverse ecosystems. Research on these birds enhances our understanding of their biology, Behavior, and the challenges they face, underscoring the importance of preserving their habitats for future generations.

12. The Peregrine Falcon: A Remarkable Avian Predator

| Animalia | Falconiformes | Falconidae | Falco | Falco peregrinus |

The Peregrine Falcon (Falco peregrinus) is a swift-flying predatory bird in Washington, mostly around cliffs and urban centers. They have steely blue-gray upperparts with barred undersides in adults and neat brown banding in juveniles. Peregrines have pointed wings and can reach speeds over 200 mph, diving upon flying bird prey.

Sometimes called the duck hawk, the peregrine falcon has slate-blue upperparts with lighter barring below in adults and brown banding in juveniles. They possess long, pointed wings adapted for speed, using steep stoops when catching other birds in mid-air. Though cliff-nesting naturally, they readily use city skyscrapers. Peregrines primarily eat other birds up to the size of ducks or rock Pigeons.

In Washington, peregrine falcons breed mostly in coastal and riparian bluffs and cliffs on the eastern slopes of the Cascades. They also occupy cities, attracted by abundant rock pigeons and tall structures for nest sites. Migrating peregrines travel through most of the state in spring and fall, following waterfowl and shorebird migration routes along major river corridors.

Though recovering regionally from last century’s pesticide impacts, partners collectively help conserve Washington peregrines. Captive breeding efforts supplement wild nesting birds on natural cliffs and human-made sites. Their incredible diving speeds make the peregrine falcon the epitome of aerial prowess. Fortunately, recovery allows increased sightings of these legendary raptors across suitable habitats in Washington.

Peregrine Falcon Facts

- Given its conservation success story, research on the Peregrine Falcon has been extensive. A study in The Birds of North America Online provides a comprehensive account of the species, detailing its biology, Behavior, and conservation status. This resource is invaluable for understanding the life cycle and ecological role of the Peregrine Falcon.

- Another significant aspect of Peregrine Falcon research is their breeding behavior and the factors influencing their reproductive success. A study in The Condor investigates egg size, hatchling sex, and clutch sex ratios in Peregrine Falcons, offering insights into their reproductive strategies and population dynamics.

- The Peregrine Falcon’s diet primarily consists of birds, which they catch in mid-air, showcasing their incredible aerial agility. Their role as apex predators in various ecosystems is crucial for maintaining ecological balance.

The Peregrine Falcon is a testament to successful conservation efforts, having recovered from the brink of extinction due to DDT poisoning. Today, they thrive in diverse habitats, from urban skyscrapers to coastal cliffs, symbolizing resilience and adaptability.

13. The Merlin: Agile Hunter of the Skies

| Animalia | Falconiformes | Falconidae | Falco | Falco columbarius |

The Merlin (Falco columbarius) is a small, stocky falcon that occurs in Washington year-round, breeding and wintering statewide. Often seen in open country, merlins have dark brown upperparts with paler streaked undersides in adults and heavy dorsal streaking in slim juveniles. They catch birds and insects mid-air in rapid pursuit flights.

Approximate American Robin-sized, the Merlin has a squat shape with pointed wings, streaked underparts, and a notched tail. Males have bluish backs, while females and young merlins are various shades of brown overall. They prey almost entirely on other birds caught in flying attacks, including warblers, sparrows, swallows, and starlings. Merlins tenuously recovered from the impact of 20th-century pesticides on reproduction.

In Washington, merlins breed locally in forest openings, often nesting on old corvid stick nests high in conifer trees. They also winter anywhere statewide with grouse, songbird, or shorebird food sources and ample perches for hunting. Ideal habitats span conifer forests, aspen groves, alpine meadows, steppe plains, agricultural lands, suburban parks, wetlands, and coastal environs.

Merlins once nested more widely in Washington before northeastern populations declined greatly. Though slowly increasing locally, small population size and reproductive issues necessitate continued monitoring. Reduced competition and increased songbird prey from land development lately aid merlins regionally. Sightings remain intermittent statewide but encounters reward birders with Merlin’s dashing speed and deadly prowess on the wing.

Merlin Facts

- Merlins are notable for their hunting style. Unlike larger falcons, they rely on speed and agility to catch their prey, mainly small birds. Their hunting flights are fast and low, often surprising their prey with sudden and swift attacks.

- As secondary consumers, Merlins play a crucial role in their ecosystems, helping to regulate small bird populations and maintain balance. Their presence also indicates the environment’s health, as they are sensitive to changes in habitat and prey availability.

- Despite their prowess, Merlins face several challenges, including habitat loss and the use of pesticides, which can affect their prey and, in turn, their own survival. Conservation efforts focus on habitat preservation and monitoring population trends to ensure the stability of their numbers.

With its striking speed and agility, the Merlin is integral to Washington’s avian community. Understanding and preserving the natural habitats of these birds is essential for maintaining the ecological balance and the health of avian populations in the region.

14. The Sharp-shinned Hawk: A Nimble Hunter of Washington’s Forests

| Animalia | Accipitriformes | Accipitridae | Accipiter | Accipiter striatus |

The Sharp-shinned Hawk (Accipiter striatus) is a small woodland accipiter breeding in coniferous and mixed forests across Washington state. Adults have blue-gray backs with rusty barred undersides, and juveniles are brown above with pale streaks below. These diminutive hawks adeptly chase songbirds through dense vegetation.

About the size of a large songbird, sharp-shinned hawks have barred gray and rusty plumage with a rounded tail, allowing agile flight maneuvering inside forests. They prey primarily on small woodland birds caught after concealed surveillance followed by rapid top-speed pursuit in dense cover. When migrating, they also eat insects, reptiles, and small mammals.

In Washington, sharp-shinned hawks occupy conifer and mixed forests statewide yet avoid higher elevations. They chase agile avian prey like sparrows, warblers, and finches inside dense tree canopies. Conservation necessitates monitoring impacts from logging pressure and climate change on suitable breeding habitats for this elusive raptor.

Discerning sharp-shinned hawks requires diligence, given their secretive, quiet habits and resemblance to similar juveniles, especially Cooper’s hawk. Patient birders may observe lightning-quick pursuits within forests ending with plucking small bird prey items from vegetation tangles. Such glimpses of focused hunting help reveal the consummate adaptation of the sharp-shinned hawk among Washington’s woodland raptors.

Sharp-shinned Hawk Facts

- A significant study in the Journal of Field ornithology evaluates the conservation status of the Sharp-shinned Hawk in Puerto Rico, providing insights into the species’ broader ecological challenges. This research underscores the importance of habitat conservation and monitoring for these birds.

- As documented in the Wilson Journal of Ornithology, the nesting habits of Sharp-shinned Hawks in urban areas highlight their adaptability to changing landscapes. This study reveals how these hawks successfully breed in urban environments, offering a unique perspective on urban wildlife dynamics.

- In Washington, the Sharp-shinned Hawk is known for its remarkable hunting skills. These hawks often prey on smaller birds at bird feeders, showcasing their agility and speed. Despite their prowess, they face threats from habitat loss and environmental changes, making conservation efforts crucial for survival.

The Sharp-shinned Hawk is vital to Washington’s ecosystem, playing a key role in controlling small bird and rodent populations. The studies on this species provide valuable insights into their Behavior, ecology, and the challenges they face, emphasizing the need for informed conservation strategies.

15. The American Kestrel: A Dazzling Predator of the Skies

| Animalia | Falconiformes | Falconidae | Falco | Falco sparverius |

The American Kestrel (Falco sparverius) is the smallest North American falcon in diverse open and wooded habitats across Washington state. About the size of a mourning dove, kestrels have colorful plumage with rusty-barred backs and wings in males and gray wings in females. These diminutive falcons prey on insects, small mammals, and birds.

The male American kestrel is conspicuously patterned with a blue-gray head, rusty-red back, wings with black spots and bars, and whitish undersides. Females have a rusty-streaked gray head, duller gray wings, and light ventral barring and streaks. Despite their small size, kestrels feed on various reptiles, amphibians, insects, scorpions, small birds, voles, and mice. They readily use nest boxes.

In Washington, American kestrels occupy open terrain like steppe shrublands, pastures, meadows, parklands, and mountains up to alpine habitat. They perch conspicuously on wires, poles, and branches and hunt by hovering before dropping upon prey. Nesting kestrels choose cavities in trees, rock crevices, dams, or buildings. Though still Washington’s most common falcon, kestrel numbers have declined recently from habitat loss, large-scale pesticide usage impacting prey, and invasive species reducing nest sites.

The American kestrel’s diminutive stature and fierce hunting abilities endear it as a fascinating raptor to observe. Colorful males make striking additions to landscapes when targeting prey from roadside perches. Yet their locally declining conservation status should elevate attention on reversing regional habitat issues for sustaining Washington’s tiny falcons.

American Kestrel Facts

- A study in The Auk explores the migration strategies of American Kestrels, revealing how factors like sex, body size, and winter weather influence their migratory Behavior. This research provides valuable insights into the adaptive strategies of these birds.

- The habitat associations and seasonal abundance of American Kestrels on the southern High Plains of Texas have been detailed in the Journal of Raptor Research. This study enhances our understanding of their habitat preferences and population dynamics, which can be extrapolated to their Behavior in Washington.

- The impact of local weather conditions on the reproduction of American Kestrels has been investigated, underscoring the influence of environmental factors on their breeding success. This research, also published in the Journal of Raptor Research, highlights the sensitivity of American Kestrels to climatic variations.

With its distinct hunting style and bright plumage, the American Kestrel is a beautiful bird to observe and a subject of significant scientific interest. The research on this species sheds light on their migration, habitat preferences, and reproductive strategies, contributing to our broader understanding of avian ecology and conservation needs.

16. The Golden Eagle: A Regal Presence in Washington’s Skies

| Animalia | Accipitriformes | Accipitridae | Aquila | Aquila chrysaetos |

The Golden Eagle (Aquila chrysaetos) is a massive dark brown raptor found breeding and hunting in mountainous and open terrain across Washington state. They have a golden wash over the back of the head and neck, with plumage darkening through molts as birds age. Golden eagles primarily eat mammals and birds located while soaring over expansive views.

Identified by the namesake golden head and neck feathers, golden eagles have dark brown body plumage overall. These huge raptors use their 6 to 7.5-foot wingspans to soar while scanning expansively for prey activity. They mainly eat jackrabbits and squirrels, supplemented by other mammals like foxes, fawns, and birds, including game birds and carrion. Breeding pairs build immense platform stick nests on cliffs, with nests reused and expanded for years.

Far-ranging golden eagles maintain breeding territories anchored on cliff nests in open habitats throughout Washington’s mountains and shrub-steppe regions. Bright golden juvenile plumage gradually darkens through molts as birds mature. Despite living up to 30 years, they can complete 500,000 high-soaring miles exploring vast hunting grounds. Approximately half of Washington’s golden eagle population migrates seasonally, while others remain resident year-round.

Though recovering from last century’s impacts, Washington’s golden eagles signify wild grandeur across the state’s interior and mountains. Their commanding nests harboring the next generation inspire conservation efforts upholding habitat integrity for Washington’s regal eagles.

Golden Eagle Facts

- A study in the Journal of Raptor Research explores the nesting territory distribution of Golden Eagles in the Southern Great Plains, particularly in wind energy landscapes. This research is critical for understanding how renewable energy development impacts these majestic birds.

- Another significant aspect of Golden Eagle ecology is their diet. In a fascinating study, a pair of Golden Eagles was observed supplying fish as food for their nestlings. This observation, detailed in the Journal of The Yamashina Institute for Ornithology, sheds light on these raptors’ varied diet and adaptability.

- The Golden Eagle’s nesting habits and courtship behavior are also subjects of interest. A study in the Raptor Journal provides a detailed description of building a new nest. It offers new data on the courtship behavior of Golden Eagles, contributing to our understanding of their reproductive strategies.

The Golden Eagle in Washington is not only a symbol of power and beauty but also an important species for ecological research. The studies on this species provide invaluable insights into their Behavior, habitat preferences, and the impact of human activities, emphasizing the need for conservation efforts to protect these majestic birds.

17. The Barred Owl: A Mysterious Nocturnal Hunter

| Animalia | Strigiformes | Strigidae | Strix | Strix varia |

The Barred Owl (Strix varia) is a stocky woodland owl species in forest habitats across much of Washington state. They have brown and white vertical striping on the abdomen and horizontal barring across the neck and upper breast, with dark brown eyes accentuating black rings. They feed mainly on mammals, birds, and amphibians.

Identified by vertical and horizontal brown and white barring, barred owls also have dark brown eyes against black rings with no ear tufts. The bill is dark gray, and the legs and toes are feathered. They emit a distinctive hooting call, “Who cooks for you, who cooks for you all?” Barred owls breed in tree cavities often created by woodpeckers, laying 2-4 smooth white eggs.

These Washington owls primarily inhabit mature deciduous and mixed forests statewide. They are increasingly adapting to secondary forests and wooded parks. These vocal owls often call to maintain contact and declare territory holdings. Strong, barred breasts distinguish them well when viewed from below when perched or flying under canopy cover.

Though barred owl numbers are increasing regionally with maturing forests, range and habitat use continue expanding in Washington. And they rival the northern spotted owl, intensifying conservation attention. While adaptable to some disturbance, losing old-growth forests still impacts nesting barred owls long-term. Their inquisitive hoots float through many forests as Washington’s easily recognized “classic” owl.

Barred Owl Facts

- One study in The Condor addresses the expansion of Barred Owl populations in Northern California, which has implications for management interventions in habitats similar to Washington. This research underscores the importance of monitoring and managing their populations to maintain ecological balance.

- Barred Owls’ impact on other species is significant. A study in Northwestern Naturalist documents an instance of a Barred Owl preying on a western spotted skunk, shedding light on their diverse diet and predatory Behavior.

- DNA metabarcoding research in Biological Conservation reveals the threat posed by rapidly expanding Barred Owl populations to native wildlife in western North America. This study is crucial for understanding the ecological impacts of this species and guiding conservation strategies.

- The Barred Owl in Washington is an intriguing species that plays a complex role in the ecosystem. Research on these birds provides valuable insights into their Behavior, diet, and ecological impacts, emphasizing the need for informed management and conservation practices.

18. The Great Horned Owl: An Iconic Night Hunter

| Animalia | Strigiformes | Strigidae | Bubo | Bubo virginianus |

The Great Horned Owl (Bubo virginianus) is a large, adaptable owl found across virtually all habitats in Washington state. They are mottled brown overall with prominent ear tufts, yellow eyes, and an orange beak. As opportunistic hunters, great horned owls eat a wide range of prey, including rabbits, skunks, geese, herons, and smaller owls.

These Washington birds of prey are heavy-bodied with brown, black, and beige patterning, feathered legs, and ear tufts that often remain flattened. Reddish stripe individuals also occur. They take the widest Diversity of prey of any raptor owing to their aggressive disposition and sharp talons. Though they nest in tree cavities, great horned owls readily occupy human-made platforms.

Occupying all forest types statewide, Washington’s great horned owls thrive across developed areas, too, in habitats with adequate prey sources. Besides their eating habits, attacks by angry owl parents also effectively limit local raptors and maintain landscape dominance. Yet their success doesn’t impede nest site shortage issues confronting great horned owls regionally.

Camouflage plumes and menacing claws shroud great horned owls in mystery, fitting their reputation. Their trademark hoots epitomize the wilderness Liphar Short called home in Kent’s beloved children’s book Hoot Owl. Echoing through the landscape, the calls of Washington’s quintessential owls captivate listeners while asserting claim over extensive nocturnal hunting grounds year-round.

Great Horned Owl Facts

- A study published in Environmental Toxicology and Chemistry delves into the dietary exposure of Great Horned Owls to PCDD/DF (Polychlorinated dibenzo-p-dioxins and dibenzofurans) in Midland, Michigan. This research is significant for understanding the impact of environmental toxins on raptors. It has implications for owl populations in similar habitats.

- The Journal of Raptor Research provides a detailed analysis of the prey remains found at a Great Horned Owl roost in Bolivia. While focused on a different geographical location, this study offers insights into the varied diet of the species, which is likely similar in Washington.

- The Great Horned Owl in Washington is a powerful predator and an important indicator of environmental health. Studies on their diet and exposure to toxins provide valuable insights into their ecology and the challenges they face in the wild.

19. The Western Screech-Owl: A Cryptic Denizen of Washington’s Forests

| Animalia | Strigiformes | Strigidae | Megascops | Megascops kennicottii |

The Western Screech-Owl (Megascops kennicottii) is a short, stocky owl occupying wooded areas across much of Washington state. They have ear tufts, yellow eyes, and cryptic gray and brown mottled coloration. Screech-owls feed on insects, small mammals, birds, amphibians, and reptiles during nocturnal hunting forays.

With prominent ear tufts and yellow eyes, the western screech-owl’s plumage is variably gray or rufous. Dark streaking helps camouflage them against tree bark where they roost. They nest in tree cavities but also readily use nest boxes. Screech-owls feed on invertebrates, small mammals up to rabbits and tree squirrels, birds, reptiles, and amphibians located by acute hearing. They are named for their eerie, screeching calls.

In Washington, western screech owls occupy wooded environments statewide. Mature stands with snags and riparian areas provide ideal habitat. Yet, screech owls also utilize suburban parks and neighborhoods with trees. During nocturnal moth forays, they advertise territories with bouncy flight displays and rattlesnake-evoking calls. The diminutive owl’s eared silhouette inspires curiosity during crepuscular pursuits after emerging at dusk.

Regionally secure currently, ongoing habitat loss threatens Washington’s screech owls. Their adaptability still allows occupying urban woodlots for now. As people embrace night sounds, the spooky calls of western screech owls accent Washington’s evenings as they hunt, shrouded by darkness through wooded park trails.

Western Screech-Owl Facts

- A study published in California Birds examines the habitat-patch occupancy of Western Screech-Owls in suburban Southern California. Although focused on a different region, this research provides insights into the species’ adaptability to urban environments relevant to similar habitats in Washington.

- Another significant study in Animal Microbiome compares the microbiomes of Western and Whiskered Screech-Owls in Southern Arizona using a novel 16S rRNA sequencing method. This research contributes to understanding the health and ecology of the species, which can be applied to Western Screech-Owls in Washington.

- Nest habitat selection is crucial for the survival of Western Screech-Owls. A study in the Journal of Ecosystems and Management investigates their nest habitat selection at multiple spatial scales in Southeast British Columbia. It offers valuable information on their nesting preferences and conservation needs.

- The Western screech owl in Washington is an intriguing species with unique adaptations to both urban and wild environments. Research on their habitat preferences, health, and adaptability provides essential information for their conservation and management.

Understanding these owls contributes to our broader avian biodiversity and ecosystem dynamics knowledge.

20. The Snowy Owl: A Mesmerizing Winter Visitor

| Animalia | Strigiformes | Strigidae | Bubo | Bubo scandiacus |

The Snowy Owl (Bubo scandiacus) is an Arctic breeding owl that infrequently visits Washington in winter months. Adults have pure white plumage with variable black markings, and juveniles have darker gray-brown barred feathers. Snowy owls feed mainly on lemmings and other small tundra mammals while flying over open terrain.

Adult snowy owls are bright white overall with scattered black markings, while juveniles have darker brown barring. Females show more markings than mostly pure white males. They have yellow eyes on a flat facial disk lacking ear tufts. Snowy owls snap up lemmings and other small rodents from tundra breeding grounds, supplementing with birds and fish.

In Washington, snowy owl sightings peak every four years, coinciding with population spikes in northern prey species. Owls then wander further south, including Vancouver and the Columbia Basin region, following boom-or-bust prey cycles. These irruptive winter movements bring snowy owls temporarily into Washington’s shrublands and grasslands when food is sufficient.

Typically, highly nomadic in non-breeding seasons, periodic snowy owl visits captivate Washington birders through their magnificence. Braving the cold, sightseers revel in the white owls’ spectral glow as the owls observe roadside fields for active rodent prey. Though fleeting and unpredictable, Washington’s snowy owl influxes allow rare glimpses of the Arctic’s consummate avian hunter.

Snowy Owl Facts

- A comprehensive study in Ibis discusses the long-term population decline of this genetically homogeneous continental-wide top Arctic predator. This research provides crucial insights into the challenges faced by Snowy Owls, including environmental and climatic changes impacting their survival.

- The distinct sexual color dimorphism of Snowy Owls is explored in a review by the Journal of Raptor Research. This study delves into the evolutionary and ecological reasons behind their white plumage and the differences between males and females, offering a fascinating perspective on their adaptation to Arctic conditions.

- Another study, published in the Journal of Wildlife Management, investigates factors associated with the returns of Snowy Owls to airports following translocation. This research is particularly relevant to understanding the Behavior of Snowy Owls in human-dominated landscapes and their interaction with aviation activities.

- The Snowy Owl in Washington is a symbol of winter’s majesty and a species of significant ecological and conservation interest.

The studies on their population dynamics, plumage, and interactions with human environments provide valuable insights into their biology and the challenges they face in a rapidly changing world.

21. The Northern Saw-whet Owl: A Secretive Nocturnal Hunter

| Animalia | Strigiformes | Strigidae | Aegolius | Aegolius acadicus |

The Northern Saw-whet Owl (Aegolius acadicus) is a very small owl found year-round in forest and woodland habitats across Washington state. They have a bright white facial disk with brown streaks, a dark head and wings, and large yellow eyes. Northern saw-whet owls feed on insects, small mammals, and birds located while perching and then swooping.

Named for their call’s resemblance to a whetting saw, northern saw-whet owls reach only 15 to 17 cm (5.9 to 6.7 in) long. Their white and brown pattered faces sport vivid yellow eyes. Coloration is brown overall with a rusty breast and streaking in juveniles. Using exceptional hearing, they locate small mammals, insects, birds, and amphibians by sound during nocturnal hunts through vegetation.

Northern saw-whet owls thrive year-round in Washington’s conifer, deciduous and mixed forests. They nest in old woodpecker cavities and readily use nest boxes. Population status appears secure globally and continues increasing in Washington as maturing forests expand owl habitat.

As Washington’s tiniest owl, the northern saw-whet owl occupies urban and rural woods shrouded in mystique. Their cat-like calls both thrill and confuse nocturnal trail-goers during park outings. Lucky birders observe saw-whet owls peering out curiously when inspecting nest boxes or mist nets, their bright yellow eyes sparkling. These elusive woodland sprites persist steadfastly across breeding and wintering grounds statewide.

Northern Saw-whet Owl Facts

- A descriptive study of the Northern Saw-whet Owl’s Anatomy, Behavior, and migration patterns offers a comprehensive look into the life of these elusive birds. The research presents detailed observations about their physical characteristics and migratory behaviors, providing valuable insights for enthusiasts and researchers.

- Another study focused on the abundance and distribution of Northern Saw-whet Owls in the Southern Appalachian Mountains of Northeast Tennessee and provides an understanding of their population dynamics in a specific region. Though geographically distinct from Washington, this study offers relevant information that can be applied to similar habitats.

- Research on the Northern Saw-whet Owl’s migratory Behavior and demographics in Manitoba, as explored in the Journal of Raptor Research, is significant for understanding the species’ migration patterns and population trends. These insights are crucial for conservation efforts and habitat management.

The Northern Saw-whet Owl, a small yet significant part of Washington’s ecosystem, is a subject of continued scientific interest. Understanding their Behavior, migration, and population dynamics is essential for their conservation and maintaining the ecological balance within their natural habitats.

22. The Northern Pygmy-Owl: A Pint-Sized Predator with a Big Presence

| Animalia | Strigiformes | Strigidae | Glaucidium | Glaucidium gnoma |

The Northern Pygmy Owl (Glaucidium gnoma) is a small owl species found in coniferous and mixed forests across Washington state. They have a round head with white spots and yellow eyes, brown upperparts and wings, white underparts with rusty barring, and long tails. Northern pygmy owls feed mostly on small birds captured via short surprise attacks.

The northern pygmy owl exhibits a round head and bright eyes with two black spots resembling false eyes on the nape. These diminutive raptors only reach about 15 cm (5.9 in) long but have a 28 cm (11 in) wingspan. Using concealed ambush tactics from dense trees, northern pygmy owls surprise and grab small woodland birds in the daytime, especially chickadees, nuthatches, and woodpeckers. They also take mammals, reptiles, amphibians, and insects on occasion.

Found year-round residing in Washington’s conifer and mixed forests, northern pygmy owls occupy a range of woodland parks and mature suburban neighborhoods throughout the state. This adaptable tiny owl currently appears secure population-wise as its habitat naturally matures over time statewide. Yet habitat loss and competition with invading barred owls potentially impact northern pygmy-owls regionally into the future.

Tricking songbirds with false eyespots became an effective ambush strategy for Washington’s smallest owl. And single notes of their tooting call invite prey within easy reach of lightning-quick talons. These diminutive forest raptors continue mesmerizing birders with their hunting prowess hidden inside peaceful park woodlands.

Northern Pygmy Owl Facts

- A study published in Frontiers in Ecology and Evolution highlights the mobbing Behavior of songbirds in response to the calls of the Northern pygmy owl. This research provides insights into the interactions between these owls and other bird species, emphasizing the complex dynamics within their ecosystems.

- The nesting ecology of the Northern Pygmy-Owl in northwestern Oregon, as explored in the Wilson Journal of Ornithology, sheds light on their habitat preferences and breeding behaviors. This study offers valuable information relevant to this species’ conservation and habitat management in Washington.

- Another study in the same journal examines the reversed sexual size dimorphism among nesting pairs of Northern Pygmy-Owls in Oregon. This study is significant for understanding this species’s unique physical traits and reproductive strategies.

- The Northern Pygmy-Owl in Washington is a species of great interest due to its hunting prowess, complex interactions with other birds, and unique nesting behaviors. The research on this owl enhances our understanding of its role in the ecosystem and the need for conservation efforts to protect its habitat.

23. The Great Blue Heron: A Stately Presence in Washington’s Waterscapes

| Animalia | Pelecaniformes | Ardeidae | Ardea | Ardea herodias |

The Great Blue Heron (Ardea herodias) is a ubiquitous, large, wading bird found statewide near the shores of open water and wetlands in Washington. Adults have blue-gray and rust coloration, a yellow beak, and a distinctive crest stretching from crown to nape, with plumes dangling behind each eye. As patient hunters, great blue herons spear fish, frogs, rodents, and insects.

With long legs, necks, and dagger-like bills, great blue herons stalk shallow water to stab prey with quick jabs, swallowing it whole. Careful one-step strides facilitate their walk-and-wait hunting while conserving energy. They also fly short distances and pick prey from the water’s surface or ground. Nesting colonially, these adaptable herons occupy diverse waterways and wetlands through urban parks and farms.

Abundant year-round residing in aquatic areas statewide, Washington’s great blue herons congregate communally to breed and roost. Their large stick nests sit high in live trees on islands, over water for predator protection. Though comfortable around humans when focused on fishing, loud disturbances at nesting sites may cause colony abandonment, impacting reproductive success. Otherwise, great blue herons currently thrive across developed and wild areas.

The quintessential marsh hunter and great blue herons amplify wetland awareness through their widespread longevity, marking food chain health over time. And their success spotlights Washingtonians’ collective actions sustaining diverse, healthy ecosystems. Their commanding terrestrial grace persists inspirational from bustling city parks to remote inland marshes statewide.

Great Blue Heron Facts

- One noteworthy study focuses on the Great Blue Heron’s foraging Behavior. In particular, the paper “Great Blue Heron Forages for Fish by Bill-vibrating” published in the Western North American Naturalist, examines a unique foraging technique used by these herons to catch fish. This research provides insights into their adaptive feeding strategies and diverse methods for catching prey.

- Another study, “Utilizing the great blue heron (Ardea herodias) in ecological risk assessments of bioaccumulative contaminants”, published in Environmental Monitoring and Assessment, explores the impact of environmental toxins on Great Blue Herons. This research is significant for understanding how bioaccumulative contaminants affect these birds and highlights their role as indicators of environmental health.

- The Great Blue Heron’s habitat preferences and nesting Behavior have also been subjects of interest. The paper “Great Blue Herons in Puget Sound” analyzes the herons’ nesting habits and population dynamics in specific regions, providing a deeper understanding of their ecology and the importance of habitat conservation.

The Great Blue Heron in Washington is an emblem of the state’s aquatic ecosystems and a vital subject in ecological research. These studies offer valuable insights into their Behavior, diet, and environmental challenges, underscoring the importance of conservation and habitat management.

| Animalia | Passeriformes | Sittidae | Sitta | Sitta europaea |

Three species of nuthatch (Sitta europaea) reside in Washington state – the red-breasted, white-breasted, and pygmy nuthatches. These small songbirds have long-pointed bills adapted for probing under bark for insects. They climb agilely down trunks and branches. The plumage differs between the species – red-breasted nuthatches have blue-gray upperparts and reddish underparts, white-breasted nuthatches have blue-gray upperparts and white underparts, and pygmy nuthatches are smaller with brown upperparts and pale underparts.

The nuthatch species found in Washington include the red-breasted nuthatch, the white-breasted nuthatch, and the pygmy nuthatch. These large birds in Washington state have long, pointed bills that allow them to probe under bark for insect prey. They are able climbers, frequently moving headfirst down trunks and along branches. The plumage markings differentiate the species – the red-breasted nuthatch has blue-gray upperparts and reddish underparts, the white-breasted nuthatch has blue-gray upperparts and white underparts, and the pygmy nuthatch is smaller with brown upperparts and pale underparts.

Nuthatches are common in Washington’s forests, using specialized bills to extract insects from crevices. Their agile climbing abilities allow them to forage along trunks and branches. Washington has an ideal forest habitat for all three species, each occupying a distinct niche. The nuthatches’ constantly moving acrobatics and loud calls make them entertaining forest residents.

25. The Sandhill Crane: A Graceful Migrant of Washington’s Wetlands

The Sandhill Crane (Antigone Canadensis), known for its tall stature, striking plumage, and distinct call, is a celebrated migratory bird in Washington. These cranes, with their red forehead, white cheeks, and long, dark bills, are often seen in open fields and wetlands, especially during their migration periods.

Sandhill Crane Facts

- A Remote Sensing in Ecology and Conservation study introduces an innovative approach to automate Sandhill Crane counts using nocturnal thermal aerial imagery. This technological advancement helps accurately monitor crane populations, essential for conservation efforts.

- Research on Sandhill Crane colt survival in Minnesota, detailed in the Journal of Fish and Wildlife Management, provides insights into the factors influencing the survival rates of young cranes. Understanding these dynamics is crucial for species management and can be applied to Sandhill Crane populations in Washington.

- The Sandhill Crane’s migration efficiency and connectivity across agroecological networks are explored in the Ecosphere. This study underscores the importance of landscape connectivity in supporting their migration, highlighting the need for habitat conservation along migratory routes.

- The Sandhill Crane in Washington is a symbol of natural beauty and an important species for ecological research.

Studies on their population monitoring, survival rates of juveniles, and migratory efficiency provide valuable insights into their conservation needs. These insights are crucial for ensuring the continued presence of these majestic birds in Washington’s ecosystems.

26. The Western Tanager: A Colorful Harbinger of Summer

| Animalia | Passeriformes | Cardinalidae | Piranga | Piranga ludoviciana |

The Western Tanager (Piranga ludoviciana), with its bright plumage and melodic song, is a stunning summer visitor to Washington’s forests and woodlands. Males are particularly striking, with their vibrant yellow bodies, black backs, and fiery orange-red heads.

Western Tanager Facts

- A chapter of a book from Cornell University provides a comprehensive account of the Western Tanager, offering a detailed overview of the species. This resource covers various aspects of the Western Tanager, including its Behavior, ecology, and conservation status. It is a valuable source for understanding these beautiful birds.

- The nesting site characteristics and reproductive success of the Western Tanager on the Colorado Front Range are investigated in the Western North American Naturalist. This study is important for understanding these birds’ habitat preferences and breeding ecology, which is crucial for their conservation efforts.

- Diet-related plumage erythrism in the Western Tanager and other Western North American birds is explored in a study by California Birds. This research delves into the relationship between diet and feather coloration, shedding light on the factors influencing the striking appearance of these tanagers.

The Western Tanager in Washington is not only a symbol of the vibrant summer season but also a subject of significant ecological interest. Studies on their nesting Behavior, reproductive success, and the influence of diet on their plumage provide valuable insights into their ecology and the need for conservation efforts to protect these colorful birds and their habitats.

Frequently Asked Questions

What is a common bird in Washington State?

One common bird in Washington state is the House Sparrow. This grayish bird, known for its black and white head, is often seen in grassy areas and can feed on or near the ground.

Where can I find a list of birds in the state of Washington?

You can find a comprehensive list of birds in Washington State from sources like the Washington Ornithological Society or the Washington Bird Records Committee. They keep records of all bird species observed in the state, including the common Nuthatch and house sparrow.

How can I attract birds in Washington State to my bird feeder?

Using black oil sunflower seeds in your bird feeder is a good way to attract various birds in Washington state, including the nuthatch and house sparrow, which often visit bird feeders. A feeder near open woodland might attract a diverse bird species.

What is the Nuthatch, a bird in Washington?

The Nuthatch is a bird species that commonly lives in Washington. Its unique habit of walking down tree trunks headfirst can identify it. This bird is usually found in open woodland areas, and its diet consists of insects and seeds.

Are there any aggressive birds in Washington state?

Some bird species in Washington State can exhibit aggressive behavior, especially during the breeding season. One example is the Western Gull, which is known to protect its nesting area and can be aggressive if approached.

What types of bird feeders are common in Washington State?

Many types of bird feeders are used in Washington State. Tube feeders are popular for smaller birds like the Nuthatch. In contrast, platform feeders attract birds, including sparrows, that enjoy feeding on the ground.

What is the house sparrow, a common bird in Washington?

The House Sparrow is a small and robust bird species common in Washington State. It has a grayish body with a black and white head and can be found in urban and rural areas. These birds are often seen near the ground and feed on insects and seeds.

How do birds in Washington State nest?

Nesting habits vary among birds in Washington state. Some birds, like the house sparrow and the Nuthatch, build their nests in tree cavities, while others, such as the Western Gull, prefer to nest on the ground or cliffs. These nests are often found in open woodland or near the water.

What do young birds in Washington State eat?

Young birds in Washington State typically eat a diet of insects and seeds provided by their parents. Some common birds, like the nuthatch and house sparrow, also introduce their young to bird feeders, where they can find a variety of seeds.

Are there bird-watching societies in the state of Washington?

Yes, there are several bird-watching societies in Washington State. The Washington Ornithological Society and the Washington Bird Records Committee are prominent. They maintain a list of birds that live in the state and conduct various bird-watching events and activities.

Conclusion