| Animalia | Artiodactyla | Bovidae | Oryx | Oryx dammah |

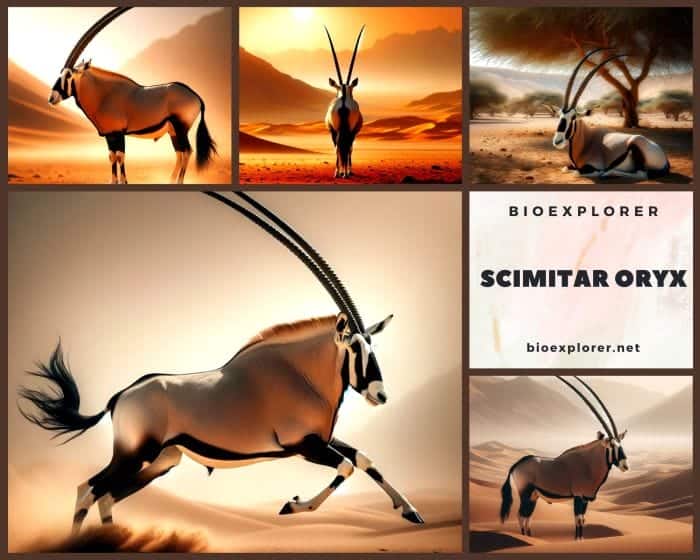

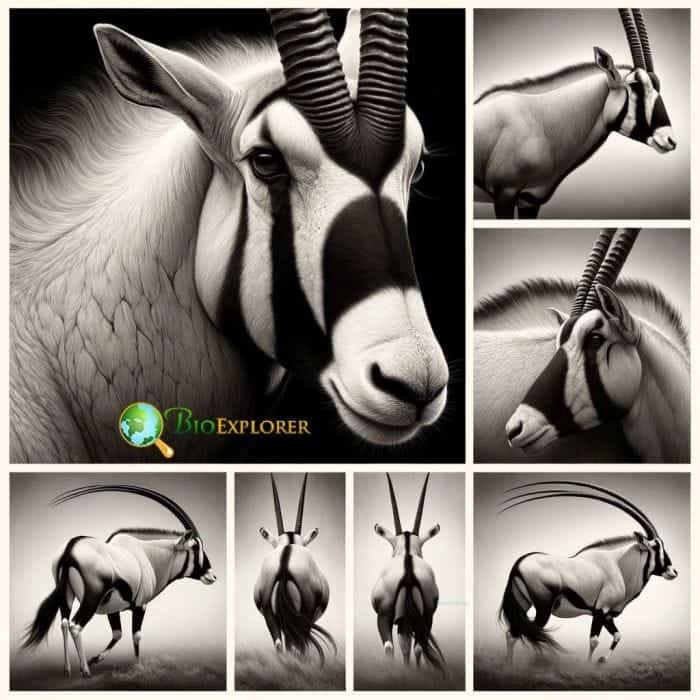

The scimitar oryx (Oryx dammah), also known as Scimitar-horned Oryx, is a large African antelope species recognized by its striking arched horns that resemble curved swords. These iconic mammals were once widespread across North Africa, but hunting and habitat destruction devastated populations over the past century. By 2000, the scimitar oryx was officially declared extinct in the wild.

However, through coordinated global captive breeding efforts, this desert-adapted ungulate has been brought back from the brink. Reintroduction programs are now working to reestablish populations in protected reserves across the oryx’s former range. Still, with all wild scimitar oryxes confined to fenced enclosures, their survival remains dependent on continued conservation focus.

The scimitar oryx possesses unique physiological and behavioral adaptations that enable it to thrive in extremely arid habitats. Rugged mountains and remote deserts provide shelter from predators and poaching pressure. But the species’ specialized needs also increase its vulnerability to degradation from livestock overgrazing and climatic shifts.

Assisted reproductive technologies and careful genetic management of captive herds present promise for sustaining scimitar oryx populations until stability in the wild can be achieved. However, health issues in captivity, ranging from parasites to deadly diseases, highlight the importance of vigilant monitoring in conservation efforts.

This article will explore the current status of the world’s rarest antelope and the multifaceted efforts working to preserve it for the future. Reversing the fortunes of this iconic Saharan species after its catastrophic decline serves as a testament to intensive conservation intervention.

Table of Contents

- Scimitar Oryx’s Unique Biology

- Scimitar Oryx Conservation Challenges and Actions

- Reproductive Technologies to Boost Captive Breeding and Reintroductions

- Health Concerns in Captive and Reintroduced Populations

- Importance of Continued Conservation Focus for Scimitar Oryx

- What Do Scimitar Oryxes Eat?

- What Eats Scimitar Oryxes?

- Fun Facts About Scimitar Oryxes

- Frequently Asked Questions

- What is a scimitar-horned oryx?

- What is the habitat of the scimitar-horned oryx?

- Is the scimitar-horned oryx extinct in the wild?

- How does the scimitar-horned oryx tolerate living in the desert for long periods without water?

- What are the conservation efforts for the scimitar-horned oryx?

- Are there other species of oryx?

- What is the status of scimitar-horned oryx in captivity?

- How does the scimitar-horned oryx use its long, sharp horns?

- How is the National Zoo and Conservation Biology Institute helping the scimitar horned oryx?

- Why does the scimitar-horned oryx have a white coat?

Scimitar Oryx’s Unique Biology

The scimitar oryx possesses various specialized physiological and behavioral traits that allow it to thrive in extremely hot, arid environments. These antelopes can efficiently conserve water and withstand remarkably high body temperatures.

Water Conservation Abilities

- Scimitar oryx can survive over 9-10 months without drinking water. Their kidneys are highly effective at preventing urinary water loss through waste.

- Instead of drinking, they get the moisture they need from wild desert plants and vegetables like melons, legumes, and cucumber-family cucurbits. For example, they obtain water from the desert gourds of the colocynth plant (Citrullus colocynthis).

- Scimitar oryx camels have a network of fine blood vessels that carry blood from the heart to the nasal passage. This allows the blood to cool by up to 5°C (9°F) before reaching the brain, one of the most heat-sensitive organs.

- They can allow their body temperatures to rise remarkably high to over 46.5°C (115.7°F) before beginning to sweat to cool themselves.

Herd Structure and Behavior

- In the wild, scimitar oryx live in cohesive family herds ranging from 2 to 40 members, generally led by a dominant adult bull.

- Both male and female oryxes have long, pointed horns reaching over 1 meter in length that help defend young from predators.

- Their social structure offers protective benefits and cooperative infant rearing.

- Scimitar oryx possess an excellent sense of smell that helps them locate sparse desert vegetation and detect rain coming from hundreds of miles away.

Physical Adaptations

- Scimitar oryx are very agile and well-adapted to steep, rocky mountain terrains in deserts and dry savannas.

- Their sure-footedness helps them evade predators in rugged habitats and access grazing resources.

- They can tolerate high temperatures that would be lethal to most mammals.

- Periodic winter snows don’t substantially impact them due to cold tolerance.

These innate desert survival skills enable the oryx to endure scorching Saharan summers and years of drought without access to drinking water. But they evolved in balance with the harsh local ecology. Disruption from livestock interference and climatic fluctuations now threatens that equilibrium.

Scimitar Oryx Conservation Challenges and Actions

The scimitar oryx once inhabited a vast stretch of North Africa from Egypt down to Niger, with an estimated historic population exceeding 1.5 million individuals. But a combination of habitat loss and rampant hunting drove the species into extinction in the wild by 2000.

Key Threats Behind Historic Decline

- Habitat Degradation: Agricultural expansion and disruption of traditional seasonal nomadic grazing patterns severely degraded dry grassland habitats.

- Unsustainable Hunting: Introducing modern weapons, vehicles, and international trade fueled excessive hunting to supply horns and meat. Local extinction followed in many areas.

- Livestock Competition: Cattle and goat overgrazing depleted vital vegetation resources and obstructed access to key seasonal water points and grazing areas.

- Climatic Shifts: Rising Saharan temperatures and intensifying drought cycles strained the oryx’s survival limits in marginal habitats.

In response, intensive and multifaceted conservation tactics were rapidly adopted to preserve surviving scimitar oryx populations before total extinction occurred:

- Emergency Captive Breeding: As numbers drastically crashed, urgent captive breeding programs were launched, resulting in approximately 1,750 oryx in managed facilities globally.

- Reintroduction Initiatives: In the mid-1990s, small reintroduced herds were established in fenced reserves in Tunisia, Morocco, and Senegal. A reserve population in Chad in 2016 now numbers over 400.

- Anti-Poaching Efforts: Armed patrols now protect reintroduced oryx in reserves from illegal hunting, alongside community engagement programs to build local buy-in.

- Habitat Restoration: Water point creation and managed rotational livestock grazing help ease resource strain and degradation from uncontrolled cattle and goat overuse.

Key Statistics on Current Status

- Extinct in the wild since 2000.

- The historic population crashed from a herd of 10,000 in Chad during the 1970s to fewer than 500 by the 1980s.

- Currently, ~4,000 individuals exist globally across captive breeding centers and reintroduction reserves.

- The largest reintroduced population is ~400 oryx in Ouadi Rime reserve, Chad, as of 2021.

Continued success hinges on sustained investment and effort to limit risky inbreeding depression in captive populations while restoring safe and sustainable habitats at reintroduction sites. Intensive management will be essential until truly wild, self-sustaining herds can be reestablished.

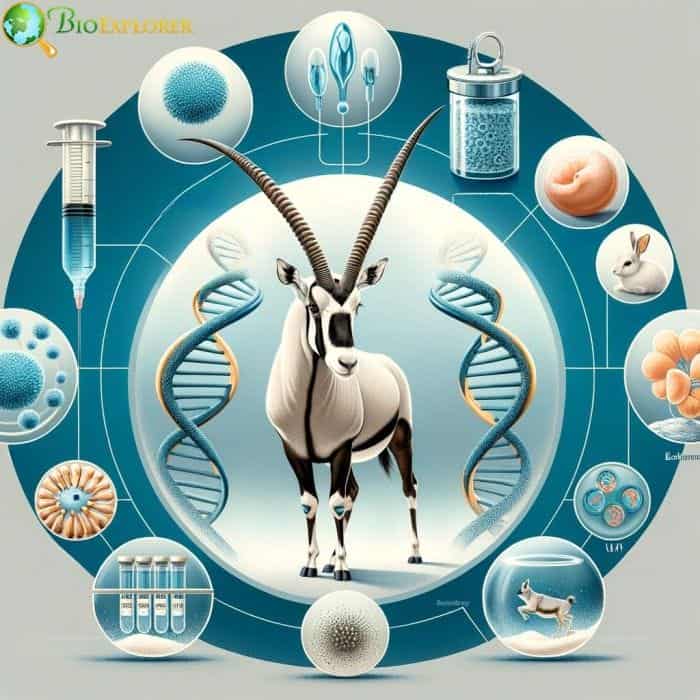

Reproductive Technologies to Boost Captive Breeding and Reintroductions

With scimitar oryx populations surviving only under intensive human management, captive breeding is crucial for preventing the complete extinction of the species. However, their long-term sustainability requires eventually reestablishing wild, self-sustaining herds through careful reintroduction from captivity into protected reserves. Assisted reproductive technologies offer important tools to advance captive sustainability and reintroduction objectives.

Key Applications of Reproductive Science

- Sperm Cryopreservation: Freezing and banking semen from wild survivors and bulls in captivity helps preserve Genetic diversity long-term in genome banks. This guards against risky inbreeding depression.

- In Vitro Fertilization: Pioneering IVF research using frozen scimitar oryx sperm has succeeded in creating viable embryos even when using cattle oocytes instead of scarce oryx eggs. This shows the potential to significantly boost founder population numbers for reintroduction efforts.

- Artificial Insemination: Carefully introducing new genetics via AI promotes genetic health within isolated captive herds without transporting live animals between facilities. This expands the accessible gene pool.

- Genetic Testing: Analyzing DNA helps guide selective mate pairings that will ensure the highest retention of gene diversity possible among offspring. Databases assist coordination.

These technologies provide conservation centers, zoos, and reserves increased flexibility and precision in managing their breeding programs and supplying optimal reintroduction candidates. Further research also continues into approaches like testing ovarian tissue grafting to retrieve viable eggs from deceased females for reproduction.

However, it is important to note that assisted reproduction cannot replace natural maternal care and behavioral learning. Calves still urgently require proper bonding, raising, and socialization from the biological mother oryx for healthy development, even if conceived unnaturally.

As such, facilitating natural herd mating and family structures remains an equally important parallel priority for supporting successful reintroduction efforts over the long term.

Health Concerns in Captive and Reintroduced Populations

While intensive conservation management has saved the scimitar oryx from outright extinction, these human interventions unavoidably carry inherent disease risks. Concentrating the entire global population into a handful of captive breeding centers enabled pathogens to spread rapidly within these dense concentrations of genetically uniform hosts.

Additionally, transporting animals between facilities for breeding purposes risks exposing new populations to unfamiliar viruses to which they have no resistance to.

Stress linked to captivity constraints and genetic inbreeding depression also play roles in making captive oryx vulnerable to outbreaks. Understanding these health threats through diagnostics testing and surveillance is thus vital.

Major Disease Issues Encountered

- Gastrointestinal Parasites: Several parasitic worms and protozoans, such as Cryptosporidium, have caused infestation outbreaks among captive calves and juveniles, which can result in life-threatening diarrhea and dehydration without swift treatment.

- Brucellosis: Bacterial pathogens like Brucella melitensis trigger reproductive issues, including miscarriages, stillbirths, and birthing complications. A 2013 outbreak in a UAE conservation breeding center impacted hundreds of oryx.

- Johne’s Disease: Hard to detect digestive infection by the bacterium Mycobacterium avium subspecies paratuberculosis causes wasting and weight loss. A 2020 outbreak in an Italian zoo resulted in six oryx deaths.

- Anthrax: The soil-dwelling bacteria Bacillus anthracis produces spores that can spark lethal septicemic anthrax outbreaks. Several historic cases have been documented in captive herds before vaccines.

Addressing these health threats requires extensive resources for strict quarantines, close medical surveillance, diagnostics testing programs, and wide-scale prophylactic treatments. Disinfection protocols and barriers to inter-facility transmission also play a vital role. However, isolating herds to allow natural immunity to develop carries its own risks.

The ultimate goal is establishing healthy populations resilient enough to thrive and reproduce without excessive interference once restored to the wild through careful reintroduction. But uncertainty remains about whether this iconic desert antelope – narrowly avoided outright extinction in the first half of the 2000s – can sustain itself without intense support.

Importance of Continued Conservation Focus for Scimitar Oryx

The story of the scimitar oryx stands out as one of the most dramatic cases of an animal brought back from the brink after near extinction.

- Its decline from widespread herds numbering over a million to fewer than 500 individuals in just decades serves as a stern warning. The success in returning global numbers to over 4,000 scimitar oryx demonstrates that drastic losses can be reversed with rapid, intensive effort. But further commitment remains vital for a sustainable future outcome.

- Ensuring the viability of both captive and reintroduced populations remains paramount. Natural habitats need protection to allow wild herds to reestablish self-sufficiency. As an iconic Saharan species that once roamed vast savannas and deserts across North Africa, the scimitar oryx belongs to the native biodiversity. Its specialized role in seed dispersal and nutrient cycling contributes to a fragile ecosystem.

- While the species’ strong cultural significance initially gave rise to its overhunting, today, it makes the oryx a symbol of successful cooperation by many nations for conservation. Its proven resilience gives reasons for hope. But these hard-fought gains could still be lost without sustained pressure against poaching and habitat threats. Many new threats like climate change and conflict also endanger the region.

The tiny anchor population in Chad’s Ouadi Rime reserve shows progress but remains a tiny fraction of historic abundance. Difficult work lies ahead to expand and connect secure habitats between regions. Creative solutions and experts’ dedication give confidence that the scimitar oryx’s extinction sentence can one day be overturned entirely.

What Do Scimitar Oryxes Eat?

The vegetation available in the arid Saharan habitats of the scimitar oryx is extremely sparse. Finding adequate nutrition year-round requires an ability to utilize a variety of different desert plants. Their diverse diets help meet water needs as well.

Major Food Sources Include:

- Grasses: Perennial desert grasses like Panicum turgidum, Cenchrus ciliaris, and Aristida plumosa dominate oryx diets when available.

- Shrubs & Bushes: Scimitar oryx browse woody plants, including acacia, caper bushes, cassia, and Tamarix africana.

- Succulents: Fleshy, water-rich plants like colocynth gourds, sesuvium, and spurges offer moisture.

- Tree Leaves & Shoots: Acacia raddiana, Balanites aegyptiaca, Maerua crassifolia, and Salvadora persica provide forage.

During the wet season, grasses account for up to 90% of the diet. As the dry season intensifies, oryx focuses on nitrogen-rich shrubs and drought-resistant succulents to compensate for nutritional deficits. Their flexible foraging allows for the exploitation of sparse grasslands and steep mountain terrain.

This varied vegetarian menu sustains the oryx year-round without requiring access to drinking water for months. But vegetation density still impacts their numbers, as degrading rangelands struggle to support herds.

What Eats Scimitar Oryxes?

As the largest antelope inhabiting the central Sahara Desert, adult scimitar oryx have few predators outside humans that can threaten them. The young, old, injured, and isolated become vulnerable to large carnivore attacks. Their herds and horns deter most threats.

Major Natural Predators Include:

- Lions: Prides sometimes prey on juvenile oryx when easier options are unavailable. Their numbers also suffered declines outside protected areas.

- Leopards: Solitary leopards stealthily ambush unattended calves and weaker subadults under darkness.

- Spotted Hyenas: Packs attack isolated outliers driven from the herd’s safety in coordinated pursuits.

- Cheetahs: Sprinting after fleeing subadults allows cheetahs to swiftly bring down tiring targets if no refuge is reached.

- Desert Wolves: Snapping at heels to hamstring legs allows wolf packs to take down older and lame oryx stragglers.

However, habitat loss and hunting by humans with modern weapons inflict far higher mortality rates on scimitar oryx populations than any natural predation. Preventing further poaching and regional extinction remains paramount for the species’ survival. The steep decline of the 20th century witnessed deer numbers crash long before major carnivores disappeared.

Maintaining a balance between rebounding predator populations and reintroducing oryx herds through conservation management will restore functional, self-regulating desert ecosystems.

Fun Facts About Scimitar Oryxes

- Both male and female scimitar oryxes have long ringed horns that can reach over 1.2 meters (4 feet) in length! Among the longest horns of any antelope species.

- Their common name comes from their gracefully curved horns, which resemble the curved “scimitar” swords used in Persia and the Middle East.

- Scimitar oryx gather in family herds of 2 to 40 members, often led by a dominant adult bull male during seasonal migrations between grazing areas.

- An excellent sense of smell helps scimitar oryx locate sparse vegetation and detect rain from over 100 miles away to aid their desert survival.

- The oryx was driven to near extinction due to demand for their iconic long horns, coveted as trophy possessions and traditional ceremonial objects.

- Urgent 20th-century conservation efforts brought the scimitar oryx back from the brink after populations that once numbered over 1.5 million crashed to less than 500 by the 1990s.

- Several successful reintroduction programs are now working to rebuild scimitar oryx numbers in protected nature reserves in Morocco, Tunisia, Senegal, and Chad.

- The distinctive mammal is the animal symbol of the Sahara Conservation Fund a partnership organization working to conserve habitats and species across the vast Saharan region.

Frequently Asked Questions

What is a scimitar-horned oryx?

A scimitar-horned oryx, also known as oryx dammah, is a species of Oryx that was once widespread across the Sahara Desert. It has a neck that has a white coat that reflects sunlight and they use their long, sharp horns, which resemble a scimitar, for defense.

What is the habitat of the scimitar-horned oryx?

The scimitar-horned oryx is a desert antelope that was once widespread across the Sahara Desert, the Sahel, Chad, and Niger. They can adapt to hot, dry environments and can go for long periods without water.

Is the scimitar-horned oryx extinct in the wild?

Yes, the scimitar-horned oryx is listed as “Extinct in the Wild” on the IUCN Red List. The last documented wild individual was shot in Chad in 2000.

How does the scimitar-horned oryx tolerate living in the desert for long periods without water?

The scimitar-horned oryx can tolerate an internal body temperature as high as 46°C, which prevents them from sweating and losing water. They can also extract most of their water requirements from the food they eat, which allows them to go for long periods without water.

What are the conservation efforts for the scimitar-horned oryx?

Conservation efforts include zoo breeding programs, such as at the Smithsonian National Zoo and Conservation Biology Institute and in Abu Dhabi. There have also been reintroduction programs in Tunisia, Morocco, and Senegal, including in the Achim Faunal Reserve.

Are there other species of oryx?

Yes, other species of oryx include the Arabian oryx and the Sahara oryx. These oryx species, like the scimitar-horned oryx, are also adapted to live in dry, arid environments.

What is the status of scimitar-horned oryx in captivity?

Many scimitar-horned oryx are bred in captivity as part of conservation efforts. These captive-bred oryx are often reintroduced into their native habitat as part of ongoing reintroduction programs.

How does the scimitar-horned oryx use its long, sharp horns?

The long, sharp horns of the scimitar-horned oryx are a key defensive feature. They use these horns to defend themselves against predators.

How is the National Zoo and Conservation Biology Institute helping the scimitar horned oryx?

The Smithsonian’s National Zoo and Conservation Biology Institute is involved in a breeding program for the scimitar-horned oryx. They also research their behavior and biology to better inform conservation efforts.

Why does the scimitar-horned oryx have a white coat?

The scimitar horned oryx’s white coat reflects sunlight, helping them stay cool in the hot, arid environments of their native habitat.

The dramatic decline of the iconic scimitar oryx serves as both a sobering reminder and a hopeful case study.

Their modern extinction in the wild warns of the extreme fragility of even highly adapted species to emerging threats like habitat destruction and over-exploitation. Yet the success of last-ditch captive breeding efforts also demonstrates that even collapsed populations on the absolute brink can be revived with rapid, intensive intervention driven by public concern.

Much work remains to build up numbers from a few hundred captive individuals to resilient, free-ranging herds of thousands once again inhabiting their ancestral dry grasslands and deserts. Real uncertainties persist about whether truly wild populations can fully reestablish themselves across the species’ former range.

However, each year, new generations are born that have never known fences, and with them comes optimism. Every calf embodies an investment into a brighter future where the scimitar oryx takes its rightful place again, roaming the Sahara it evolved to survive and thrive within.

The public fascination that spelled tragedy for the antelope now fuels its protection. With continued engagement, innovation, and political dedication, the second chance afforded this narrow survivor by temporary shelter within our institutions can lift their sentence, restore their homelands, and create space for the oryx and all wildlife to flourish again.