| Animalia | Aves | Passeriformes | Corvidae | Chordata | Corvus hawaiiensis |

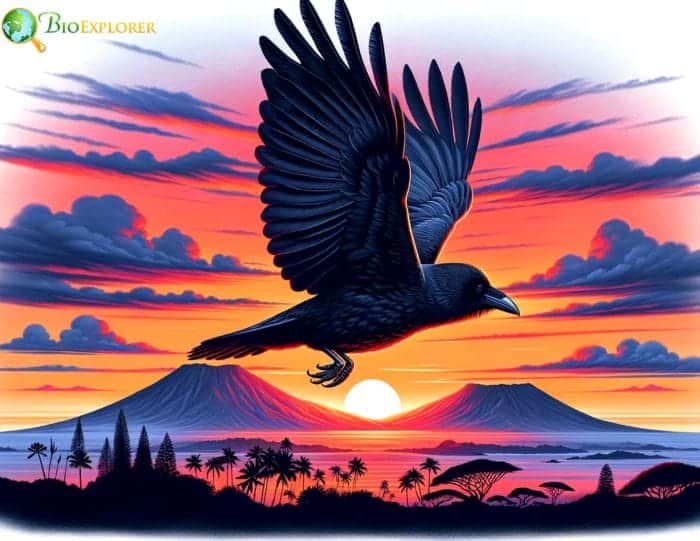

The Hawaiian crow, or ʻAlalā as it is known in Hawaiian, is a fascinating bird native to the Hawaiian Islands. This intelligent and resourceful corvid was integral to Hawaii’s native forests for thousands of years.

However, habitat destruction, invasive species, and disease have decimated the population, leaving the Hawaiian crow on the brink of extinction. Today, less than 150 individuals remain in captivity.

While the outlook is grim, there is still hope through dedicated conservation efforts. This page will take an in-depth look at this remarkable bird – its unique adaptations, challenges, and why restoring Hawaii’s native crow matters now more than ever.

Table of Contents

- Basic Facts About the Hawaiian Crow

- The Decline of the Hawaiian Crow

- Unique Adaptations of the Hawaiian Crow

- What Do Hawaiian Crows Eat?

- What Eats Hawaiian Crows?

- Conservation Efforts to Save the Hawaiian Crow

- Why the Hawaiian Crow Matters?

- Fun Facts About the Hawaiian Crows

- Frequently Asked Questions

- What is the ʻalalā, and why is it significant?

- Where can the ʻalalā be found in the wild?

- What are the main threats to the ʻalalā population?

- Is the ʻalalā currently part of any conservation programs?

- How does the San Diego Zoo contribute to ʻalalā conservation?

- What are some of the successes of the ʻalalā reintroduction efforts?

- How do efforts to save the ʻalalā affect the broader ecosystem in Hawaii?

- What is the natural predator of the ʻalalā?

- Can the public visit areas where ʻalalā are being reintroduced?

- How can individuals contribute to the conservation of the ʻalalā?

- Conclusion

Basic Facts About the Hawaiian Crow

- Scientific Name: Corvus hawaiiensis.

- Size: 16-18 inches long with a wingspan around 2 feet.

- Coloring: Jet black feathers covering the entire body.

- Distinctive Features: Curved, crow-like beak. Short square tail. Highly sociable and forms family groups.

- Habitat: A variety of native Hawaiian forest habitats, including wet forests, dry forests, and high-elevation woodlands.

- Diet: Omnivorous eats insects, snails, fruits, seeds, small reptiles, eggs, and young birds. Flexible and opportunistic foragers.

- Role in Ecosystem: Played an important role in seed dispersal and controlling pest populations. Their decline has impacted forest regeneration and insect balance.

Some key facts highlight the Hawaiian crow’s distinctive traits as Hawaii’s only endemic corvid species. Their jet-black appearance and curved beak resembling the American Crow earned them the nickname “Hawaiian crow”. However, they are their own unique species.

Some key facts highlight the Hawaiian crow’s distinctive traits as Hawaii’s only endemic corvid species. Their jet-black appearance and curved beak resembling the American Crow earned them the nickname “Hawaiian crow”. However, they are their own unique species.

Evolutionary adaptation to Hawaii’s remote environment allowed them to fill an important niche in forest ecology. Their inquisitive nature, intelligence, strong social bonds, and family-oriented society also set them apart from mainland crows. Sadly, many of these wonderful traits contributed to their vulnerability once humans drastically altered their homes.

- Common Name: Hawaiian Crow.

- Scientific Name: Corvus hawaiiensis.

- Conservation Status: Extinct in the Wild (IUCN Red List[1]).

- Year Discovered: 1825

- Discoverer: Naturalist Andrew Bloxam[2].

- Taxonomist: Titian Peale, 1848.

- Size: 16-18 inches long.

- Wingspan: Around 2 feet.

- Plumage Color: Jet black.

- Native Habitat: Hawaiian wet and dry forests.

- Diet: Omnivorous insects, snails, fruits, seeds, small reptiles, eggs, young birds.

![]()

The Decline of the Hawaiian Crow

The Hawaiian crow was once abundant across the Hawaiian Islands, with an estimated population of hundreds of thousands. These intelligent birds thrived in a variety of forest habitats. However, human activity beginning in the late 18th century set the species on a tragic decline from which it has never recovered.

Several key factors led to the catastrophic decrease in the Hawaiian crow’s numbers:

- Habitat Destruction: Logging of native sandalwood forests and clearing of land for agriculture destroyed much of the forest habitat the crows relied on. Deforestation left them more vulnerable.

- Introduction of Non-Native Species: Pigs, goats, and cattle degraded land and competed for food sources. Predators like rats, mongoose, and cats preyed on crows and eggs. Diseases from mosquitoes also impacted the birds.

- Disease: Avian malaria carried by introduced mosquitoes decimated crow populations without natural immunity. Po’ouli disease may have also contributed to the decline.

By 2002, habitat loss, predators, and disease had taken such a toll that the Hawaiian crow became extinct in the wild. The population dwindled from a peak of hundreds of thousands to less than 150 birds surviving in captive breeding facilities. Urgent intervention is required to bring this iconic Hawaiian endemic back from the brink.

![]()

Unique Adaptations of the Hawaiian Crow

The Hawaiian crow evolved remarkable abilities to thrive in its island forest home before human contact:

- Foraging Behaviors: Their strong curved beaks allowed them to probe and pry bark to catch insects and larvae. Dense scruffy feathers protected them from abrasions while foraging.

- Vocalizations: Hawaiian crows had a complex array of over a dozen different call types used to communicate. Their frequent cheerful vocalizations earned them the Hawaiian name “ʻAlalā” meaning “to call”.

- Differences from Mainland Crows: Hawaiian crows lived in family groups and bred cooperatively, unlike American crows. They were also less wary of people initially.

- Evolutionary Adaptations: Adjustments over time allowed them to inhabit a wide elevation range and varied ecosystems. They filled an important niche as scavengers and insect controllers.

- Intelligence and Tool Use: Hawaiian crows are resourceful and can use sticks and other objects to probe for food. Their brains are large relative to their body size.

Sadly, the traits that enabled the Hawaiian crow’s success also increased their vulnerability to foreign diseases and human pressures. However, their resilience shows why bringing them back is still possible if swift conservation action is taken.

![]()

What Do Hawaiian Crows Eat?

The Hawaiian crow evolved as an omnivorous generalist forager capable of exploiting various food sources. Their diverse diet included:

- Insects and larvae: Crows probed decaying logs and swept their bills through vegetation to catch insects. Some favorite prey included beetles, moths, crickets, centipedes, and spiders.

- Snails: Plentiful land and tree snails provide a good source of protein. Crows used tools to extract snails from shells.

- Fruits: Native ʻōhiʻa tree berries were a key food year-round. They also ate fruits from the naio and Koa trees.

- Seeds: Various seeds from native plants and berries supplemented their diet.

- Eggs and Nestlings: Crows occasionally raided nests of smaller birds for eggs and chicks.

- Small vertebrates: Lizards, frogs, and invertebrates added protein.

- Carrion: Dead animal matter provided an opportunistic food source.

Their flexible foraging habits allowed them to take advantage of food resources in wet and dry forests across different elevations and seasonal conditions. This adaptability contributed to the crow’s evolutionary success before recent human-caused pressures.

![]()

What Eats Hawaiian Crows?

As an endemic island species, the Hawaiian crow evolved with relatively few natural predators compared to mainland crows. The main predators preying on crows before human arrival included:

- Hawaiian Hawks: Also known as ʻio, these native crested honey buzzards potentially preyed on crows, especially juveniles and eggs. However, the crows’ watchful family groups likely offered protection.

- Hawaiian Short-Eared Owls: These agile owls likely ambushed some crows at night and took nestlings. Their numbers were relatively small, however.

- Hawaiian Eagles: The largest Hawaiian owl, Madamoiselle, could take crow fledglings, though they were not a major threat.

Once humans introduced mammals, the number and impact of predators increased dramatically:

- Rats: Black, Norway, and Polynesian rats all preyed on eggs and nestlings. Being arboreal, rats could access nests.

- Feral Cats: Roaming cats took eggs, chicks, and some adults. Cats spread to forests via human settlements.

- Mongoose: Introduced small Indian mongoose, which decimated native ground birds and may have occasionally attacked crows.

Habitat degradation also left crows more vulnerable to predation from native hawks and owls as forests were cleared. The increased predation pressure contributed to the severe decline in crow numbers.

![]()

Conservation Efforts to Save the Hawaiian Crow

With the Hawaiian crow population declining to under 150 birds in the 1990s, urgent action was needed to pull the species back from the brink. Several intensive conservation initiatives aim to restore wild populations:

- Captive Breeding Program: The Alala Project runs dedicated breeding facilities in Hawaii and Maui, housing the entire population. Careful genetic management produces chicks annually.

- Predator Control: Before reintroduction, non-native predators like rats and cats are trapped or poisoned around release sites.

- Disease Research: Scientists study malaria resistance and work on treatments to protect crows from disease.

- Supplemental Feeding: Providing food sources at release sites helps establish crows until they can forage independently.

- Predator-proof Enclosures: Large enclosed aviaries allow crows to acclimate in the wild, protected from predators and disease[3].

- Habitat Restoration: Partners replant native trees and vegetation that crows rely on in reintroduction areas.

- Community Engagement: Outreach and education foster public support for conservation efforts. Hawaiians see the crow as a cultural treasure.

While the path to recovery remains challenging, innovative approaches combined with traditional ecological knowledge offer hope of restoring the Hawaiian crow to its vital role in the native forests.

![]()

Why the Hawaiian Crow Matters?

While the Hawaiian crow is critically endangered, there are compelling reasons why it is worth saving:

- Cultural Significance: The crow represents a vital part of Hawaiian mythology and traditions. It is considered a family guardian or ʻaumakua in Hawaiian culture. Restoring the bird has deep meaning.

- Keystone Species: As scavengers, insect controllers, and seed dispersers, crows filled a crucial ecological niche in forest ecosystems. Their decline impacted biodiversity.

- Indicator of Forest Health: Thriving crow populations indicate intact native forests. Their absence signals wider environmental problems.

- Endemic Wildlife: As an endemic species, the Hawaiian crow deserves protection. Over 75% of Hawaii’s native birds are already extinct.

- Ethical Responsibility: Since human actions pushed crows to the brink, we bear responsibility for restoring them. Each species has inherent worth.

- Ecological Balance: Hawaii’s ecosystems developed harmoniously with the crow over millennia. Their unique services contribute to overall forest health.

Losing the Hawaiian crow would represent the disappearance of a culturally and ecologically important piece of Hawaii’s natural heritage. Simple justice demands we do all we can to give this remarkable species a second chance.

![]()

Fun Facts About the Hawaiian Crows

The Hawaiian crow displays some fascinating behaviors and traits worth highlighting:

- Hawaiians specifically bred crows to produce birds with beautiful black plumage perfect for making feather capes and cloaks worn by alii[4] (royalty).

- Legend says the Hawaiian crow’s jet-black color symbolized its ability to travel between the realm of the gods and earth, acting as a messenger between realms. This spiritual role gave them revered status.

- In Hawaiian mythology, the crow was considered an ‘aumakua or family protector spirit that could shapeshift. It was believed the crow could read people’s inner thoughts and see the future[5].

- The Hawaiian crow has an average lifespan of 20-25 years in the wild, significantly longer than that of similarly sized birds. Their strong family bonds likely contributed to this longevity.

- Young Hawaiian crows played games like tossing sticks high up in the air and catching them. They also rolled down slopes repeatedly. This reveals their intelligence and social nature[6].

- The Hawaiian crow has over a dozen distinct vocalizations used to communicate different messages between individuals. Their frequent and cheerful calls inspired their Hawaiian name, “ʻAlalā”.

- Kamapua’a, the Hawaiian demigod associated with fertility and agriculture, was said to take the form of the Hawaiian crow as one of his many animal transformations[7].

- Kāmau and Lono are two Hawaiian akua (gods) embodied in the form of ‘alalā and celebrated in oli (chants[8]). They represent revelry and agriculture.

- The endemic koa and ʻōhiʻa trees that Hawaiian crows depend on are considered kinolau the living embodiment of important Hawaiian gods and ancestors.

- In Hawaiian proverbs, the wisdom and prudence of the crow are emphasized through sayings like “He ‘alalā ka’ā manu kāma’āina a kū’ono’ono” meaning the crow is a native bird that observes carefully before acting.

![]()

Frequently Asked Questions

What is the ʻalalā, and why is it significant?

The ʻalalā, or Hawaiian Crow, is a critically endangered bird species native to Hawaiʻi. It holds significant cultural importance for Native Hawaiians and is crucial for the ecological health of the island’s forests. The species has been part of a comprehensive conservation program due to its status as an endangered bird.

Where can the ʻalalā be found in the wild?

The ʻalalā used to be found in the wild across the Big Island of Hawaii but is now extinct in the wild. Efforts to reintroduce the species are ongoing, focusing on areas like the Pu’u Maka’ala Natural Area Reserve on Hawai’i Island.

What are the main threats to the ʻalalā population?

The main threats to the ʻalalā population include habitat loss due to human activities, predation by introduced species such as the Hawaiian hawk or ‘io, disease, and a low genetic diversity among existing populations. The decline of the ‘alalā has also been attributed to the loss of natural food sources and environmental changes.

Is the ʻalalā currently part of any conservation programs?

Yes, the ʻalalā is part of the Hawai’i Endangered Bird Conservation Program, which involves organizations such as the San Diego Zoo Wildlife Alliance, the State of Hawai’i Division of Forestry and Wildlife, and the U. S. Fish and Wildlife Service. These conservation programs focus on breeding efforts, habitat preservation, and reintroduction initiatives.

How does the San Diego Zoo contribute to ʻalalā conservation?

The San Diego Zoo, through the San Diego Zoo Wildlife Alliance, plays a significant role in the conservation of the ʻalalā by participating in the conservation breeding program and researching their behavior. They have successfully bred these birds in captivity and have been working towards their reintroduction into their natural habitats on Hawaiʻi Island.

What are some of the successes of the ʻalalā reintroduction efforts?

One of the major successes of the ʻalalā reintroduction efforts has been the release of captive-bred ʻalalā into protected areas of Hawaiʻi, like the Pu’u Maka’ala Natural Area Reserve. Several birds have survived post-release and have begun to exhibit natural behaviors such as foraging and nest-building, indicating positive adaptation to the wild.

How do efforts to save the ʻalalā affect the broader ecosystem in Hawaii?

Saving the ʻalalā is critical not only for the species itself but also for the entire forest ecosystem in Hawaiʻi. As natural seed dispersers, the ʻalalā play a role in the regeneration and health of native plant species. Their conservation directly impacts the biodiversity and ecological balance in Hawaiian forests.

What is the natural predator of the ʻalalā?

The natural predator of the ʻalalā is the Hawaiian hawk, or ‘io. However, introduced predators such as feral cats, rats, and mongooses also pose significant threats to the ʻalalā, especially to young birds and eggs.

Can the public visit areas where ʻalalā are being reintroduced?

Public access to reintroduction sites such as Pu’u Maka’ala Natural Area Reserve is generally restricted to minimize disturbances to the ʻalalā and other native wildlife. However, special programs or guided tours may be available through conservation agencies that allow limited public interaction while ensuring the birds’ welfare.

How can individuals contribute to the conservation of the ʻalalā?

Individuals can contribute to the conservation of the ʻalalā by supporting organizations involved in the ʻalalā project, participating in wildlife conservation donations, spreading awareness about the plight of this endangered bird, volunteering with local conservation groups, or even by visiting conservation centers where one can learn more about the efforts to save the ʻalalā and other native Hawaiian species.

![]()

Conclusion

The Hawaiian crow stands as a unique and iconic bird deeply woven into Hawaii’s natural and cultural fabric. This endemic species faces grave threats from habitat loss, invasive species, and disease, pushing it to the brink of extinction. However, there is hope for the future through dedicated conservation efforts focused on captive breeding, ecological restoration, predator control, and community engagement.

The Hawaiian crow persists as a testament to the intelligence, flexibility, and social bonds that enabled it to flourish for eons before human disturbance. We bear the ethical responsibility to give this culturally treasured and ecologically important species a second chance. With immediate action and continued stewardship, the remarkable Hawaiian crow may return to its rightful place in Hawaii’s native forests.